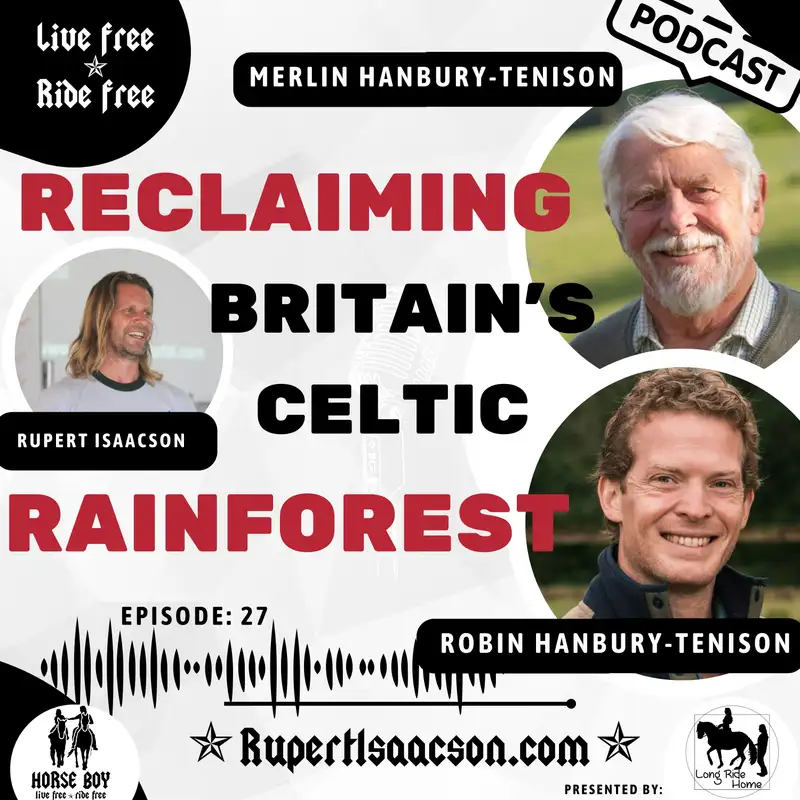

Reclaiming Britain’s Wild Heart | The Celtic Rainforest with Robin & Merlin Hanbury-Tenison | Ep 27

Rupert Isaacson: Thanks for joining us.

Welcome to Live Free, Ride Free.

I'm your host, Rupert Isaacson, New

York Times bestselling author of

The Horseboy and The Long Ride Home.

Before I jump in with today's guest, I

want to say a huge thank you to you, our

audience, for helping to make this happen.

I have a request.

If you like what we do here,

please give it a thumbs up,

like, subscribe, tell a friend.

It really, really helps

us to make the pro.

To find out about our certification

courses, online video libraries,

books, and other courses,

please go to rupertisakson.

com.

So now let's jump in.

Welcome back to Live Free, ride Free.

I've got the legend, Robin

Handbury Tenon and his son Merlin.

Today, if you don't know who Robin

Handbury Tenon is, you might know

actually some of the work he's done.

But he's been a bit of a ance,

squeeze a power behind many beneficial

effects on the planet and on peoples.

And it's very dear to my heart because

those of you who know my story know that

I worked for a long time with Sun Bushman

in the Kalahari, helping them get legal

title to their ancestral land after

they'd been illegally evicted in Botswana.

And had it not been for the British

organization, survival International.

Who we did all our British work through.

We did some of it in America,

some of it in the uk.

There would have been nothing.

And the man behind Survival

International who founded it is the

man sitting here, Robin Bury Tenison.

So I owe a great debt of gratitude.

But we all do.

And the reason is because the sand

bushmen actually are common ancestors.

If they had disappeared off the

planet, which they were in grave

danger of doing back in the early

two thousands, that would be like

us losing touch with ourselves.

They are the original oldest

culture on the planet.

And it's easy to kind of think roll

your eyes at something like that,

but you don't miss it till it's gone.

And about every generation there

are threats to people like this.

And a man like Robin.

You know, steps in and

does something about it.

And so I'm very grateful to Mr.

Ry Tenon here.

And I'm very, very glad that his

son Merlin is a chip off the old

block because he's doing something

rather amazing for us all as well.

So that's my preamble.

Lads, would you tell us who you

are, what you do, and why you do it?

Do you wanna kick off?

Yeah.

Age first.

Robin Hanbury-Tenison: I think age first.

Age first.

I think, well, the other side of my life,

apart from the wonderful introduction

you gave me on, on background survival

International, which I'm hugely proud

of, and which has done so much work

in the field of indigenous people.

The other big thing I did was to lead

the biggest scientific expedition

Britain ever mount to understand

how the rainforests work in Borneo.

And I lived there for 15 months

with a great group of scientists.

We cracked the rainforest code.

We worked out why you can have this lush

rainforest going on what is effectively a

desert and why you shouldn't cut it down.

It didn't help.

It's cut it down so much over the

last 40 years since the expedition.

And but my life had been much

devoted to scientific research into

tropical rainforests, only to find

the back on my little hill farm on

Bob Monroe, which me now runs, runs.

We had the last remnant, one of the last

remnants of temperate rainforest, which

is just as rich and incredibly rare.

And so suddenly my focus, having

been on tropical, is now all

about temperate rainforests,

which Merlin will tell you about.

Rupert Isaacson: You said just now

that you cracked the rainforest

code, I just get to, I get to Merlin

a mo, but you can't say something

like that and not have me jump.

Okay.

What does that mean?

What, how do you crack a rainforest code?

What, what is the rainforest code?

Robin Hanbury-Tenison: Quite

right to pick me up on that.

For a long time, people couldn't

understand how this incredibly

rich and lush di biodiverse habitat

could exist on something which is

effectively a desert because there's

no soil under the reef forest.

There's no humus like we

used to in Northern Europe.

Okay?

There's just about an inch of soil.

And when you cut the trees down of soil

rushes away, and it becomes a desert.

How can that possibly happen?

And a lot of people were researching it,

and the big thing we cracked was to find

out how it happens and what the, the

story is that the nutrients are reabsorbed

almost instantly as they hit the ground

by all the millis and centipedes.

And, and they get caught up in

the rootlet systems and micro

are immediately back in the tree.

So the tree is containing all its

nutrients and recycling them in itself.

And therefore, it's another reason

apart from the many other reasons why

you shouldn't cut tropical rainforest

down because you will create a desert.

I'm doing

Rupert Isaacson: Wow, this I didn't know

because I would've assumed that any.

Forest that's anywhere in the

world that's sat there for some

generations must be sitting on a

massive layer of hummus, right?

Because leaves are falling, bark is

falling, biomass is falling, right?

I mean, okay, I'm gonna return to

this, but the question I'm gonna

return to, 'cause I don't, you know,

we need to find out who Merlin is here.

But the question I'm gonna pick up is,

why doesn't that happen in every forest?

Why is that specific

to tropical rainforest?

'cause now I want to know, but Merlin,

who are you and why are you here?

And what, what

do you do?

I.

Thank you so much for,

for having me here Rupert.

And it's it's always challenging following

my father 'cause he casts along shadow

and has done such amazing things.

But but it, but it's a huge pleasure

and honor always to do these these

father son conversations together.

'cause he, it's wonderful

to bounce off each other.

So I, I grew up here on this,

this hill farm or Bob and Moore.

So I'm, we're both currently

sitting on the, on the farm in

the, in the heart of Cornwall.

With my father going off on these

exciting and in incredible expeditions

to far-flung tropical regions.

And when I was 19, I, I left and

joined the army and it was at a

time when the military was, was very

busy in the early two thousands.

And I subsequently went on three

tours, three combat tours of

Afghanistan in quite quick succession.

And on one of these I was blown up

in a, a roadside bomb by the Taliban

and was very fortunate to come

away physically, almost unscathed.

And, and to continue an enjoyable military

career before leaving the army to, to get

married and going and working in London.

And it was while working in

London that I began to suffer

from quite poor mental health.

And, and some of that was experiences in,

in the military especially being blown up,

coming back to haunt me in a form of PTSD.

But, but much of it was also related to,

I think, what's far more recognizable

to most people, which is just the

stresses and the pressure and the, in

many ways, unpleasantness of working

in these fast-paced urban environments.

Mm-hmm.

And I was extremely lucky

that I had cabilla this.

Gorgeous valley in the heart of Bob

and Moore with this slice of Atlantic

temperate rainforest, a term that

we weren't even that familiar with

at the time in the heart of it.

And I was able to retrieve into that

space and come and hide down there and

heal down there and, and, and really

fall in love, re fall in love 'cause it

had been the playground of my childhood.

But, but really begin to understand

how important these habitats are.

And at the same time my wife Lizzie and

I were trying to start a family and she

was going through problems which are,

are all too common and far too little

understood and, and, and suffering from a,

a couple of really traumatic miscarriages.

And she was using this valley

as a place of healing for her.

And then a couple of years later,

and I'm sure we, we may come onto

this, but my father got very, very

severe COVID back in 2020 and was

sedated for seven weeks in hospital.

And we were told by the doctors that

he was almost certainly gonna die

and wasn't gonna come back to us.

He was already in his mid

eighties at that point.

He is extremely old.

And and we were told there was no

way he was gonna come home and.

That boy immediately, sir.

Rupert Isaacson: And,

and he he, he did come home.

I mean, he is remarkable for his

age though, and he, and he, he

healed within this forest as well.

And so we had these three stories of

my personal psychological healing,

my wife Lizzie's, psychological and

physical healing, and my father's

physical healing within this habitat.

And it set me on an obsessive path to

not only bring more people into the

Atlantic temperate rainforest that we

had at Cabilla Veterans with P ts d.

This is what Lizzie and I were obsessed

about, bringing veterans with PTSD women

on their fertility journeys, nurses

from the NHS, suffering from stress

and burnout, corporate professionals

going through the same challenges

we've been going through, but also

to elevate, highlight, restore,

and protect this habitat because.

The point that I really love here is

that my father has made this point.

He just disappeared off screen.

I hope he is not upset coming down.

Exactly.

He's not upset with anything I've said.

But we, we all know whether you are eight

or 80, we all know about how important

tropical rainforests are and how they

are the lungs of the planet, and how

they are our most important habitats

that are being degraded and deforested.

And the reason we know that is because

of many, many expeditions that have been

run, but my father's ones especially,

which have cracked the rainforest

code and shown us that the tropical

rainforest, like the Amazon and Borneo

are the lungs of the planet and the most

important habitat from a biodiversity

and a climate mitigation, and a a, a

general planetary equilibrium perspective.

And so we all, when we hear

the word rainforest, we think

of places like the Amazon.

We've forgotten that actually once

Britain was a rainforest island, 20%

of the United Kingdom was a rainforest

landscape just a few thousand years ago.

And my mission, my dream is to help

to be a part of reminding everybody

that Britain is a rainforest island

and we are a rainforest people.

And it should be as important to us

as it is to the people of tropical

countries who have rainforest very

much as a part of our culture.

And that is why we started our

business, Camilla Cornwall, and our

charity of a thousand Year Trust

and the work that we're doing now.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay, so I just

want this, this podcast goes out

across the English speaking world.

So not everyone knows what Cornwall is,

and not everybody knows what Bob Moore is.

And not everybody knows that

there are temperate rainforests.

So just for the listeners, I want you

to picture when you think of Lord of the

Rings and you see elves coming through

the Misty Feny, mossy Bouldery, greeny.

Thing that's a temperate rainforest.

And the reason why it has that miasma

is actually water that 'cause it's a

very, very high rainfall area where the

UK sits juts out into the Atlantic and

sits in what's called the Gulf Stream

because we're actually on a, on a, on a

latitude with kind of Northern Alaska.

And if it wasn't for

that, we'd be shivering.

But no, we, we, we have

this high rainfall.

Some people say it's rather gloomy and

gray, but it's not dissimilar to the

Pacific Northwest in the US or British

Columbia, coastal British Columbia.

So, so if you think about that,

so if you've watched Vikings or

if you watch the Lord of the Rings

and you, they went to temperate

rainforests and they filmed there.

So whether it was in New Zealand,

whether it was in Canada for Vikings

and there are pockets of this still

left in the uk and it's something

I've been aware of for a long time.

Because I used to, although

I was brought up in.

Partly in London and partly in

Leicestershire, which is on the

eastern side of the uk, which does

not get that particular climate.

So North Sea climate gets scoured by

the winds from Siberia, this western

Celtic side of the planet, which all

the Celts got pushed into by the Romans.

So therefore, it has all the

sort of mysterious mythology

and spirituality as well.

All kind of combine to

this rather magical thing.

This magical thing is what you all

are looking to revive and protect.

No.

That's absolutely right and

you are, you're quite right.

Fand Forest is a temperate rainforest,

Jeffrey of Monmouth Arthurian Legends,

the ma ian Lewis Carroll's jab walkie.

These are all set within

temper rainforest.

These are rainforest myths.

We just weren't using that term.

And they are not only our most folkloric

and, and allic habitats for that

reason, but they're also a pinnacle

habitat for many scientific reasons.

So they are our most carbon sequestering

habitat that we can restore and

plant territory to terres in the uk.

So they suck more CO2 outta

the air than anything else at a

time of high climate challenge.

That's really important.

We're also in the uk, the

most nature depleted country.

In Europe and, and temperate rainforest

restore that biodiversity abundance,

which is so important and bring

back that layering of life better

than anything else we can restore.

But I think most importantly, they are

the best habitat that we have in the

UK for the mental health and wellbeing

of humans who spend time amongst them.

And a lot of our science scientific

research that we are doing here

is focused on that human element.

I think that's so important.

Rupert Isaacson: Alright, so

you, Robin, let's go back to you.

You, you, you said that you'd cracked

the tropical rainforest code, which

was that the trees are self-sustaining

units that when they drop their

humus, the humus gets reabsorbed.

There's a re-uptake immediately.

So isn't humus layer, but this presumably

is not the case in a temperate rainforest.

What's the difference?

Why do you have that in a tropical one?

Why do you not have that one in?

I'm sitting in Germany right now

and I'm looking at it very large.

Beach forests.

Okay, so probably beach forests.

Yeah.

That I live in.

There's definitely a

big humus layer there.

So what, what created this rainforest

thing that's tropical that does not

have that humus layer, which, 'cause we

know that humus also sequesters carbon.

No.

And then why does a temperate

rainforest sequester so much carbon?

Why is it not the same thing just colder?

Robin Hanbury-Tenison: Well,

you're not alone in, in, in

not understanding how it works.

And I had a wonderful occasion when I had

take Margaret Thatcher then prime Minister

around a, a, a picture of artistic

exhibition of paintings in the rainforest.

And we were looking at these wonderful

paintings of rich, lush rainforest

for all intensity of life within it.

And she said to me, such a shame.

We have to cut that, all that down.

But then we said, we need

the agricultural land.

I had wonderful opportunity of being

able to say, rubbish prime minister, and

actually knowing what I was talking about.

And she looked a bit shocked and nearly

handbagged me and said, what do you mean?

And I had to explain to her

that tropical rainforests exist.

We now understand through recycling

all the nutrients, instantly,

they never go into the soil.

Whereas temperate forests and agriculture

generally in northern Europe and where

we have humus growing up, as you've just

said, and there is a depth of humus up

to 4, 5, 6 feet in bends, but usually two

or three feet in normal areas, you have

this humus and this soil from which is

sustainable and on which the trees grow.

And so when you cut them down, you just

park more and grow, they grow again.

It's a completely different cycle,

temperate from tropical rainforest.

And that was what people

really didn't understand.

And one of the reasons why there was such

immense destruction of tropical rainforest

in the search fatigue and timbers.

Even though in the, in the old days, the

bad old days or good days, you see it, the

colonialism, the, the people responsible

used to recognize it in a sort of way.

And instead of, and you had a

conservator of forests whose job

was to hand out timber concessions

for only 1% of the area of time.

And then to allow it to naturally

regrow, which we only had a 1% happen.

It was sustainable.

Nowadays it's greed and density of

modern commerce in the far east and,

and South America and Africa, indeed.

The tropical rainforest is being

destroyed all the time, and we are being

left with a, a dessert an eroded desert

behind which is totally economically

and socially and biologically stupid.

Yeah.

But

there is there, there is a, a, a

nice crossover and similarity between

the tragedy of what's happened in

Tropical Rainforest and the tragedy

of what's happened in temperate

rainforest, which is the introduction

of non-native grazing mammals.

And so many of, much of the Amazon

rainforest has been cut down in

order to create space for cattle

pasture and cattle grazing.

And, and the cow is a completely

non-native creature to South America.

So these have been imported.

They don't fit within the trophic system.

They don't have natural predators,

natural competitors and, and the

things that they forage on don't

have a way of responding to them.

They do very unnatural things to

the ground, which has been one of

the things that's really destroyed

these tropical rainforest landscapes.

In the same way in Western Europe and

in the UK in particular, much of our

temperate rainforest was cut down.

Longer ago, so two,

three, 4,000 years ago.

Whereas in Brazil, it's been in the last

few centuries in order to make space for

sheep, sheep grazing, which is really

all that tends to happen on the uplands

once the temperate rainforests have gone.

And the sheep in exactly the same way that

the cow is non-native to South America.

Sheep are entirely

non-native to Western Europe.

They're a Mesopotamia and a a Persian

import that was brought along Silk Road

roots four and a half thousand years ago.

And they are a very well evolved

desert animal, which as a result

of being a desert animal, have very

small hooves, which compact the soil.

When they step upon it,

they're voracious appetites.

'cause when you live in a desert,

you eat everything you can find

and their manure isn't beneficial

to temperate rainforest soil.

So we've done a very similar

thing by taking the trees away and

putting cattle in South America.

There's been the same effect

in Western Europe by taking the

trees away and placing sheep in

Rupert Isaacson: Western Europe.

That's interesting.

I'm just, as you were saying,

they're not native to Western Europe.

I'm just sort of going through, 'cause

in, in this area of Germany I live in,

we have some muon, which is English.

English.

It's, you know, European wild sheep.

Up in the low mountain

range that we live in here.

But yes they're sort of widely

acknowledged to be a Mediterranean.

Yeah.

Wild species that was sort of

naturalized here, perhaps by

the Romans or earlier, you know.

But, and I'm just trying to think

of the cave walls of Lascoe and

those other Western European

paleolithic rock art repositories.

And I'm just sort of going through in

my mind, have I seen sheep on those?

We see horses, we see cows, we see bison,

we see bears, we see wolves, we see lions.

Do we?

A few, a few,

few, few Woolie rhinos and

straight tus elephants as well.

Right?

Right.

But, but no sheep.

But we don't, and, and it comes

back and I'd never, I've never

Rupert Isaacson: stopped

to think of that before.

And on our charity here, the thousand

Year Trust, one of the reasons that

we came up with that name was because

when I started talking about this

subject, people would go, well, hang on.

Sheep have been here for four

and a half thousand years.

Surely that's long enough for them

to be considered native or, or, or,

you know, part of the evolutionary

system within this island.

But that is not the way

evolution or Mother Nature works.

They, the human timelines that we feel

comfortable working within five, 10,

a hundred years are completely out of.

Perspective with actually how

natural systems function and work.

And so we have to have the, the, the

appetite, the boldness, the objectivity

to be able to look in island landscapes.

And I've always entertained by the

difference between places like New

Zealand and Australia and Te del

Wago, other island habitats, where

the people who live there are very

comfortable saying, this species evolved.

Here it is native, this species

was introduced by humans, it is

non-native and therefore it should

be either removed or suppressed.

In New Zealand, they were, they have

competitions amongst schoolchildren to

bring in as many rats that they've killed,

and they get a competition for the one

that's brought in the most in the uk.

If we did that with gray squirrels at

schools you know, the, the tabloids

would hit the roof and, and everyone

would be being fired from their jobs.

We, we, I think we have a real timidity

in the UK about looking at the flora

and fauna that we have across our

islands and saying actually that

that is non-native and therefore it

might be being destructive and sheep.

A brilliant example of that,

just like gray squirrels are and

things like rhododendron and,

and in many places, beach trees.

Rupert Isaacson: Now of course,

we've, we've built the beginnings

of the British Empire on wool.

Mm.

You know, the, the medieval period, as

you know, we, we grew wool here in the uk.

Say, here I'm sitting in

Germany, but, you know, sold it

to Flanders, the low countries.

It was then processed and went

out, and that was the basis of the

prosperity upon which we built the

next thing, which was to cut all the

ship forests down to make ships, oh,

go and be pirates around the world.

And then they called

that the British Empire.

Now that's gone, but we now have

a bank instead, as we know which

causes people great stress.

And they go and then get their mental

health back in your rainforest in, in

Cornwall, in the southwest of England.

But you guys have a large farm.

You're sitting up there on

Bob Min Moore and Boman Moore.

For those who the listeners, what

you need to understand is Cornwall,

actually, this is what you need

to understand about Cornwall.

If you dunno the UK.

People and Cornwall talk

like, ah, a little bit.

And Pirates talk like that too.

Why?

Because they come from Cornwall.

So Cornwall is the bit of

southwest England that sticks

out furthest into the Atlantic.

So if you were going to be on a ship and

get down and steal gold from the Spanish

ships coming back from the Caribbean

back in the 16th century, probably

you came from that southwest corner of

the UK around Portsmouth and then west

into Cornwall and it's smugglers and

it's 'cause it's a rocky coastline.

You can hide things in caves and

that's why we have the pirate accent.

So if you didn't know that, okay,

and you'll hear it alive and well in

any pub in Cornwall, but Boman Moore,

where Robin and Merlin are sitting is

a mountain spine, like a low mountain

spine that runs along the center of

that peninsula and then it goes down

basically to the coast on either side.

You guys are sitting up there.

Are you honest?

Are you saying that you are going

to take your farm like the whole

thing just co you know, it's a

couple of thousand acres or so.

Are you going to, are you gonna

re rainforest that whole thing?

Like, you've already done it.

Is that what you're gonna do?

Are you doing So it's, it's a lot.

It's not that big.

It's a smaller farm.

It's it, it's, it's become

smaller over the years.

Yeah.

And, and now it's about 250 acres.

And, but I find that very,

Rupert Isaacson: very exciting.

So you, you, you, the whole lot

sheep

Rupert Isaacson: gone.

Back to the break for us.

She gone and we've, we've reestablished

a hundred thousand trees across the farm.

So few listeners, an acre is about the

size of a football or a soccer pitch, so

that's 250 football pitches all stitched

together and laid over this valley.

And the average size of a farm

in the UK is about 220 acres.

Yeah.

So we are 250 acres, but a hundred acres

of that, or about 85 acres of that is

already atlantic temperate rainforest.

So actually our farmable

land is only 160 acres.

And the important thing about that

is that there are many charismatic

and really exciting and innovative

nature restoration Rewilding projects

in the uk, but they tend to be very,

very large areas of land, three, four,

5,000, 20,000 acres up in the Highlands.

And they're often owned by people who

are doing something quite philanthropic.

They have the resources and

the funds to, to do something

quite high risk and innovative.

That doesn't necessarily make money

because we have a, an average sized farm

in a very challenging farming environment.

What we do has to work.

EE ecologically and economically

for the farmers that do it.

So what we are creating is a blueprint

for a future of upland farming, which

transitions sheep popped green tarmac,

which has very little biodiversity and

very little health and, and life and

vitality, and also is very, very bad

for flooding and droughts downstream

because it doesn't hold water in the

uplands very bad for soil climate,

bad climate change, big rain event.

Yeah,

absolutely.

Very bad for water quality.

And we've plant, we've

reestablished, we've planted 40,000

trees, we've got 60,000 coming

back by natural colonization.

So it's a hundred thousand tree site.

We've turned that 165 acres back into a

cadet rainforest that is establishing.

And the way, the reason we're doing that

is to be able to show our neighbors and

other farmers around us that this is

actually a better way to manage their

land, both ecologically and economically.

And, and that can turn much

larger rows of land back into

temperate rainforest landscapes.

Rupert Isaacson: But

what is the economics?

How would someone make money?

So for example, again, for the listeners

who might not know farming in the uk

like farming in Europe and farming in

many parts of the world is subsidized.

So if you come from an upland area,

which is traditionally sheep farming,

as you say, you would get a certain

subsidy from the government to,

you know, keep running your sheep.

And then in addition to that, you would

obviously be selling some for meat and

some for wool, and blah, blah, blah.

And that's your livelihood.

How, how do you make money by

turning it back to rainforest?

Because if it's not making

money, people won't do it.

That's a great question.

And as my father well knows, having

farmed up here for 50 years and tried

lots and lots of very innovative

different types of farming, farming

in the uplands is not a, a profitable

endeavor on, on an average sized farm.

And when, when I moved down, when my

wife and I moved down about 10 years

ago, we looked at this very, very closely

and ran all the numbers and tried to

understand how we could make a living

and raise a family and do something

that was ecologically beneficial on this

small patch of, of Moreland or Upland.

And we found, I found that the

average Upland Hill farmer on Bob and

Moore and Dartmore currently takes

between 85 and 92% of their annual

income from European subsidies.

This was when I was looking at this 10

years ago before we left, before Brexit.

Yeah.

Before Brexit, now that we've left

the European Union, all of those

subsidies have been taken away.

They've solely, incrementally gone down

until in 2027 they stopped completely.

And the British system that's replacing

them is, is, is a fraction of the

generosity of what we, of what we were

given before by the European Union.

The average age of a farm around

here is in their mid sixties.

It has the second highest suicide

rate of any job type in the uk.

The younger generation are

not taking these farms on.

It is almost impossible to make a living.

So before I answer the question about

how you make a living from upland

farming by reforesting, it's important

to establish that as a baseline.

People are not making a living from

this kind of farming at the moment.

So it's not outside.

Outside of the subsidies, right?

Yeah, outside of the subsidies.

So it's not like we're taking, you

know, wildly profitable upland hill

farms and wrecking them into rainforest.

Actually, what we're doing is transferring

them into an agroforestry model.

So we're still farming this land.

There'll be a native breed conservation

grazing scheme of cattle and horses

and pigs that move through the

rainforest because trees need large

animals, and large animals need trees.

And this is a very weird thing that

we've done with farming in the UK

where we consider healthy farmland

to be fields with no trees and large

animals and healthy woodland to be lots

of trees with no large animals, when

actually they all evolved together.

Trees benefit from having animals

rubbing against them and foraging

amongst, encompassing them.

And the animals benefit from the shade

in the summer, the shelter in the winter,

and the additional forage that they get.

So we still have animals passing

through it, or we will have there's

also now a very important financial

model for farmers around, around

carbon sequestration and the carbon

markets around biodiversity net gain.

And also with the work we do at Cabilla

Cornel, where we've brought over 3000

people into the rainforest at Cabilla.

There are ecotourism opportunities, which

I think is really the next moment for

the farmed landscape because there's such

an inequality of access to wild spaces

for many people who live in the uk.

Rupert Isaacson: Well, let's talk about

that because you guys both know, I mean,

you're landowners and not everybody is,

and I did 20 years, I had a ranch in Texas

for 20 years, and one of the big issues

there is there's no land access, right?

You, you either own it

or you can't go on it.

I mean, you might have the odd

neighbor who lets you take a walk

or ride your horse or something,

and if you go on it, you get shot.

You definitely get shot.

Yeah.

And in fact, if they paint the top of

the fence post purple, it means they'll

shoot on site and not challenge you.

So there's a lot of that, you know,

and the sound of automatic fire at

the weekends and that sort of thing.

The UK actually does have, by

comparison, really good access.

I know there's a, a debate that

rages in the UK about, you know, we

don't have access to the countryside.

I actually call BS on that.

Because if, if, if you've ever lived

in a place where you don't have that

kind of access, even Ireland, you

don't really have that kind of access.

Yeah.

But in the UK there's a big network

of footpaths and most of the open

hill areas you can kind of walk.

And let's face it, if you do walk on

someone's land, you might get yelled

at, but you certainly won't get shot.

And if you're not a complete dick and like

let your dog chase the sheep or something

and leave all the gates open, probably

people are actually relatively tolerant.

If you were to, I'm going to

throw this one at you Robin.

So let's say you evangelize Cornwall

and Cornwall becomes one big temperate

rainforest up there on bottom mage.

I'd love to see because then I'm thinking

I'm fantasizing about wolves and bears and

things like that coming back, which I dig.

'cause the wolves just came back

to our area in Germany and it's

quite exciting how not all of those

farmers can make the same money

from the same ecotourism outfit.

There's only so much glamping you can do.

Right.

So unless the entire population of

London decamps, although I suppose in

some ways it does to the beaches what's

the model for ensuring that there's.

A sort of a broader economic benefit,

not dissimilar to the current subsidies,

because that, that's the obvious

question, is, okay, you guys have put

in an infrastructure, you're very well

connected, you, you know how to do these

things but your neighbor might not.

And then they might resent the fact

that the business is coming to you.

How do you Yeah.

How do you, how do you democratize

it so that it takes the, really

takes the place of the sheep?

Robin Hanbury-Tenison: Well, there

actually are subsidies still, the

subsidy system has changed from

being subsidizing land ownership or

production as it was under Brexit.

And there's a new thing called elms,

environmental Land Management, which

encourages people who look after.

So it's, it's rewarding people.

Looking after nature rather

than for exploiting it.

And are those

Rupert Isaacson: subsidies just quickly,

are they, are they comparable to what

their people would currently get?

They, they're

Robin Hanbury-Tenison: not

comparable, but they're there.

They're great.

Yeah.

And there are all sorts of

other things that people can do.

I mean, I've been banging

on about this for years.

I used to have a very feisty New

Zealand partner who was, was really into

exploiting every kind of possible D of

avenue on the farm, Bo Goats and Red Deer

and Wild Boa and all sorts of things.

And he was very into using the,

the land to its maximum good

New Zealand Kiwi philosophy.

And we used to argue a lot about it.

And I would say this was 40, 50 years

ago, I was saying to him the day

will come when you will be receiving

more benefit from environmental land

management than you will from production.

And he would say, that's rubbish love.

And we had lovely

discussions about all that.

It is happening.

And there is now so much awareness

as Melon has been saying about the

beneficial attributes of proper

landscape, of, of associating with

nature, both the mental and physical

and, and pure enjoyment reasons.

And indeed a recognition of how

over exploited we have been through

agricultural production of our

land and how depleted we are in

wildlife and plants and insects.

I mean insects for example.

I dunno if you can

remember it world or not.

Remember the days when we used

to have things called little

buggers on the front of our cars.

Yeah.

Which were a little deflective things

which removed huge numbers of insects

that otherwise built up on the windscreen.

Don't need those boy

hardly ever get insects.

Insects have been catastrophic decline.

Mm-hmm.

So

Robin Hanbury-Tenison: there are many,

many aspects why this whole new vision

of farming makes very good sense.

And, and I think you know, to to,

to add to that, one of the potential

negatives of the European subsidy

system that we've been in since the

early seventies in the UK is that it

was very focused on food production.

And, and if you ask any farmer across

most of the eu, but certainly in the

uk, what their job is, they'll say the

job of a farmer is to feed the nation.

It is to produce food.

And actually, when you start to look at

a little bit more closely at, at what

that looks like across the uk where we

have all of these different topographies

and types of soil quality and and, and

weather patterns, we produce 20% of our

food from 3% of the land in the uk and

that's all in East Anglia, Lincolnshire,

you know, Norfolk, places like that.

We then use 22% of the uk,

which is the Western reaches.

Or sheep production, which

produces less than 1% of our food.

So we're doing something very strange.

We then, a third of our food goes into

landfill and 40% of our land is exported.

So we, we we're, we're behaving quite

strangely, and I believe that the

job of a land steward, or a farmer,

or a landowner is multifaceted.

It is drought prevention, flood

prevention, clean water, clean air, clean

soil, food production, timber production,

beautiful places for people to spend time.

The problem is, at the moment,

farmers are only paid for one or two

of those really just for producing

food and maybe for producing timber.

We need to move to a system where

actually, if we accept that farming will

always, or land management will always

be subsidized, which it probably always

will because we have an expectation

across the western world for a price of

food, which doesn't match the price of

production or the cost of production.

So if we accept that farming will

always need some form of subsidies, it

needs to be blended across all of the

ecosystem benefits that land managers

and land stewards need to be providing.

And a big part of that is

open access and public access.

A, in a managed and controlled way.

We've all seen places.

I remember.

When I was kind of a younger man that

filmed the beach came out, and it was

so beautiful that everybody went to

this one beach in Thailand and took

photographs of it, and it was destroyed.

And in the same way with the Instagram

generation now, there are many beautiful

spots where when they become famous,

everybody goes there to get a selfie,

and that spot becomes destroyed.

And we need to avoid that happening

where the natural world is degraded

by completely unfettered open access.

And we've seen that with Westman's Wood

near us on Dartmore, which is a temperate

rainforest that has been very badly

damaged, but in the same way the days of

landowners rather like the Texan model

being able to totally fence off their

land with purple stripes across the

top of the post and keep out anybody.

I think those, those days are beyond

us and, and people who manage land

need to move with the times and accept

that we have an inequality of access.

From a mental health and a physical health

perspective, we're living through a mental

health pandemic and an obesity pandemic.

We need to encourage and facilitate

people from, especially from

inner city areas, having easy

access to beautiful wild spaces.

That's gonna be part of

the model of the future.

It has to be,

Rupert Isaacson: let's bring

it down to money though.

So, I, let's say you, you guys

are in a town hall meeting where

they're in Boman Town Hall and

I'm doing one tonight at Jamaican.

Exactly.

I'm meeting lots of farmers tonight

at Jamaica Inn and I'm gonna sit

there with my arms folded, right?

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

And and that expression with my mouth down

and be like, you soft London bastards,

you know, coming here and telling us

what to do, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.

Even though you've been there forever,

you know, nonetheless, you know, we know

how things are in the countryside often.

Alright, now you've gotta sell me.

The two things which I could see

selling me if I was a current

conservative farmer would be.

Three, well, three things really.

I think I'd want reassurance

that there's money in it.

Beyond base subsistence, meaning that,

and so then, would that be apart from

the subsidies for land stewardship,

would that also be carbon sequestration

Robin Hanbury-Tenison:

and biodiversity net gain?

Rupert Isaacson: As you know, if

you followed any of my work, I'm

an autism dad and we have a whole

career before this podcast in helping

people with neurodivergence, either

who are professionals in the field.

Are you a therapist?

Are you a caregiver?

Are you a parent?

Or are you somebody with neurodivergence?

When my son, Rowan, was

diagnosed with autism in 2004,

I really didn't know what to do.

So I reached out for mentorship, and

I found it through an amazing adult

autistic woman who's very famous, Dr.

Temple Grandin.

And she told me what to do.

And it's been working so

amazingly for the last 20 years.

That not only is my son basically

independent, but we've helped

countless, countless thousands

of others reach the same goal.

Working in schools, working at

home, working in therapy settings.

If you would like to learn this

cutting edge, neuroscience backed

approach, it's called Movement Method.

You can learn it online, you

can learn it very, very simply.

It's almost laughably simple.

The important thing is to begin.

Let yourself be mentored as I was by Dr.

Grandin and see what results can follow.

Go to this website, newtrailslearning.

com Sign up as a gold member.

Take the online movement method course.

It's in 40 countries.

Let us know how it goes for you.

We really want to know.

We really want to help people like

me, people like you, out there

live their best life, to live

free, ride free, see what happens.

Who would pay me for that?

So those, now, those are now on

very well audited and accredited

marketplaces that they're creating.

So the main one in the UK for

carbon is the woodland carbon

code, which is held by the forestry

Commission, the government body.

And so you, you plant trees and

you grow trees and you get an

independent assessment of the amount

of carbon that's being sequestered.

And then those credits can

be sold on a marketplace.

So it can be bought by anybody.

Rupert Isaacson: Could I, could I

make a fairly decent living like that?

Similar to having say

windmills on my land.

Well, you, I mean, bay going back to

that point that you can't make a decent

living at the moment from sheep, right?

Anyway, you can make a better

living from selling carbon.

And in the same way that you don't

choose who you sell your sheep to, you

sell it to a supermarket who sell it

to members of the public or consumers.

You sell your carbon, I

who set price as well.

Yeah.

On a, who sell the price.

And you sell your carbon on a

market, which sets the price,

and it is purchased by consumers.

Some of those will be businesses, some

might be members of the general public.

So it's sort of a, it's a similar

model and it's a bit nebulous.

And that's why where the challenge comes.

'cause many people will look at

that and go, well, when you're

producing wool or lamb or milk,

you can see what's being produced.

You can kind of, you can

really, you understand.

A farmer grows lamb.

They sell the lamb, someone

to lamb, it's a thing, goes to

a physical market, it's sold.

Whereas carbon and biodiversity are

less tangible, but equally as important.

Rupert Isaacson: Right?

So how do I, let's say

I'm a, I mean, I am.

Approaching Seniorness now.

So let's say I'm a conservatively

minded senior farmer.

I don't know how to navigate those market.

You know, you, you, you, you, you've

come up from the financial District

of London and you're talking a

language I don't understand at

all, and now I feel threatened.

How are you gonna help me get it?

I can really envisage

Oh, money in my pocket, like, so that,

that's exactly what our charity, so our

charity is a thousand year Trust that

I, that I founded a couple of years

ago, which is Britain's only rainforest

charity, the only charity dedicated to

the protection restoration expansion

of Atlantic temperate Rainforest.

We're working in a number

of different areas.

Our main focus is around scientific

research, just like my father's work

in tropical Rainforest in the past.

But also a lot of it is around community

engagement, stakeholder engagement,

and helping other farmers to join

clusters and schemes, landscape

recovery schemes, which is a big

Rupert Isaacson: push British,

but you said stakeholder there.

Right?

And I'm the, I'm the, I'm sitting

there even as myself and I just went

communities, communities bringing

together farmers and landowners

to say, how are you gonna help me?

Merlin?

I own this farm.

How are you gonna help

me get that carbon money?

You need to hold my hand.

You need to take me.

So, so just talk, walk me through

the process of how you'd do that.

I'm, I'm, I'm

intrigued.

So, so that's why we've done it

here to create a blueprint site.

So what I can do is say

that, come and see our farm.

Come and see Cabilla, come and have

a walk around and see the trees that

we've planted, see how the landscape is

changing, how as a result of introducing

things like beavers and bringing

back some of the biodiversity, we're

seeing less flooding, less drought.

We're seeing more biodiversity,

more inverses returning.

And then let's sit down and

in a really basic way, using a

one pager blueprint document.

Look at who we introduce

you to, who can help you.

Who are the tree planters?

Who are the government bodies

that will provide you with the

grant funding to plant the trees?

Who are the people who come and

assess you for their carbon credits?

And in exactly the same way that

farmers, farmers are very bright people.

They have relationships with

the buyers of supermarkets.

They can have relationships

with the buyers.

On the carbon market, it's the same thing.

Someone,

Rupert Isaacson:

someone's gotta make that.

No, I mean, no one, no one introduced me.

So I, I, yeah, I, I had to

figure it out and in the, but,

but now I'm sitting here, I'm

Rupert Isaacson: used to leading

parallel lies in parallel cultures.

Yeah, you are not, but now

I'm here to help them.

So I'm, I'm here my, the charity.

So are you basically,

Rupert Isaacson: that's what you do?

You, you help them?

Well, we're a charity, so

we're not doing it for a fee.

We are saying, how can we bring together

a community and help people to benefit

in the same way that we're trying to,

and as innovators, it's not an easy

Rupert Isaacson: for us, but

you act like a consultant.

You, you say, we will help you to.

Navigate this new rather confusing,

as you said, ne nebulous market.

But

there are other amazing, there

are amazing consultancies

out there doing exactly that.

And one of the things we would do

is say, look, speed it down here.

You can say, speak to the forest

for Cornwall, who are a Cornwall

council run group who are

helping farmers to transition to

more of an agroforestry model.

Okay.

You can say, look, talk to.

Yeah.

There are many people out there, natural

England, the Forestry Commission,

the Environment Agency, they're all

trying the wildlife, I dunno, people

trying help farmers these people.

It's

Rupert Isaacson: now, it's good that

you're telling me, 'cause now I can

begin to put together a mosaic, you see?

Yeah.

Rather than somebody saying, well,

you've got to do something different.

Yes.

And that's what farmers have had in

the past being told you are the enemy,

you are damaging the environment.

You need to do something different.

And farmers sit there in a really

challenging environment and no

one works harder than a farmer.

You know, I see our neighbors who

are still sheep, sheep farming

in a very serious way out at 3:00

AM every morning, picking up.

Dead lambs or, you know, helping

lambs give birth or a different,

or shearing throughout the night.

And it's hard work.

And then to say to them, now you

need to go and learn an entirely

different financial model to try

and keep your family on the land.

It's not fair.

And there are more and more organizations

setting up to help them, and we hope

to, we are one of those as well.

But it is a, it's gonna be a difficult

moment of transition, but you've

gotta come back to that point as well

of going of remembering that most

farmers are in their mid sixties.

They're looking to find an

opportunity or an excuse to hand

over to the younger generation.

The younger generation don't

want to go into a debt laden poor

profitability standard up hill farming.

The younger generation are going,

okay, we, we'll take the land Landover,

but what are we gonna do on it?

Mm-hmm.

And we are there to say, here's an

alternative and here's how you transition.

Got it.

Rupert Isaacson: Robin, I

want to this one to you.

So the other, the other concern

I would have as a, as a farmer

would be lifestyle and culture.

Sell me on if, if I, if I go over and give

a portion, a significant portion of the

land over to this rainforest idea how do I

preserve my, the culture that, the

way of life that is dear to me?

Because yes, I work very hard and yes,

I'm in debt for this, but I also love it.

I love the upland.

I love the sound of the sheep.

I love the lambing.

I love it.

There's an emotional attachment as well,

and we all know this, that, you know, I, I

partly come from a farming family as well.

It's not entirely a business thing.

It's, it's, it's, it's a,

it's a love thing as well.

It's an emotional thing.

And the attachment to the land and the

attachment to the land looking a certain

way because the, there's no question

that, that the English countryside,

even if it's lacking biodiversity, is

very, very aesthetically beautiful.

There's no question about that.

It's, it's an art.

Piece, really.

And I always feel that we,

we mess with it at our peril.

I get very depressed when I see the,

the solar panels covering fields or the

lines and lines of windmills because

it's industrializing the landscape.

Even if it's in a good cause,

it, it, my heart goes down.

It doesn't go up.

It's just the cold, hard fact.

So

sell it to us now, Robin.

How, how are you gonna preserve the

aesthetic, the lifestyle, the, the culture

Robin Hanbury-Tenison: with the forest

on, on the case of wind turbines,

they're a very emotive subject.

I got into a lot of trouble with them

because I was president of the our local

conservation organization, which started

by, I started it 60 years ago, doing all

sorts of opposing bad planning and so on.

Then they became obsessed because

a lot of 'em were run by people who

come down from London living corn.

And, and the obsession about wind

turbines became to, and all, all

the complaints they were making

were all against wind turbines.

And I made the mistake of writing a

paper telegraph saying that not all wind

turbines, I've got one here, we have one.

Can't really see it the middle very much.

And it's not a huge one, but it helps

generate the deal of electricity.

And I dare to say that not

all wooden turbines were bad.

And then I made a mistake of

carrying on with the letter.

And so after all in the Middle Ages,

every village in Britain had a windmill.

Objected to.

And I got sacked.

He rated,

Rupert Isaacson: I'm sure, yes.

That you could, could choose the,

the stake on which they impaled you.

Yeah,

Robin Hanbury-Tenison: yeah.

Well, they're now all, all, all

being very nice to them and say

We were wrong actually, because

recognizing turbine have a part.

But, and of course, plannings come into it

and they must be environmental friendly.

We also have an array of tape panels,

which I put up about 20 years ago.

And they're invisible everywhere

because I've strategically located

behind the, and see them many and they

help to, to make us almost off grid.

But I do think that there is a dichotomy

always, as there always is with planning

over where and when things should be.

And, and it upsets me to see whether

a cultural lab, other panels there's

absolutely no reason why land, but

underneath them can't be used effectively.

And I think this is a mistake making.

Cheap or geese, or wild flowers, or even

as the Japanese are doing very effectively

now growing vegetable crops underneath

panels, apparently we get because of

the reflected sunlight to actually get,

generate a better fertility for garden.

So there are lots of things

that could be happening.

It's, it's one of those

balances that has to be made.

But even at the same time, you have

access to good countryside around that.

Not necess, not necessarily that

that woodland people can walk in.

That's a better balance.

It's, it's all going to change.

Countrysides gonna look different.

I suspect that offshore wind

turbines people don't object as much

because they can't see them so much.

Yeah.

And there are other ways of I mean

every, it just astonished me for quite a

long time that, that it is not law that

every new building in the country has

to have its roots made of solar panels.

Yes.

Or the, the roads we drive on or not,

they look just like slate and tile.

Yeah.

They didn't have to look like panels.

And I, I, I simply don't understand

why that has not been made law,

because if every rooftop was generating

power, wouldn't need panels all over.

Rupert Isaacson: Absolutely.

And, and we hope that,

that, that day will come.

My neighbor actually just

got his roof redone that way.

If you made it this far into the podcast,

then I'm guessing you're somebody

that, like me, loves to read books

about not just how people have achieved

self actualization, but particularly

about the relationship with nature.

Spirituality, life, the

universe, and everything.

And I'd like to draw your

attention to my books.

If you would like to read the story

of how we even arrived here, perhaps

you'd like to check out the two New

York Times bestsellers, The Horseboy

and The Long Ride Home, and come on an

adventure with us and see what engendered,

what started Live Free Ride Free.

And before we go back to the

podcast, also check out The Healing

Land, which tells the story of.

My years spent in the Kalahari with the

Sun, Bushmen, hunter gatherer people

there, and all that they taught me, and

mentored me in, and all that I learned.

Come on that adventure with me.

But back to I'm a farmer and I want

to be sure somehow that Cornwall,

the Cornwall I know and love won't

disappear and my lifestyle is it.

So is it just as, as, is it

something as similar as as simple

as saying, well, look, yeah.

Have some sheep just not that many.

You know, what, what is it?

Because I'm very I'm a sheep farmer.

I'm also attached to sheep.

I love sheep.

I, you know, I, I race

horses, for example.

You know, I'm attached to them.

I love them.

I'm, it's, it's my thing, right?

So if you, I, I wouldn't

want to give them up, but I

might to doing it differently, you know?

As we know, you know, sheep are completely

ubiquitous across the west of the uk.

You see a postcard of Wales or of

Devon or of the peak district or

of Cornwall, and it doesn't have

sheep in it and something's wrong.

And, and, and I've been very keen always

never to look backwards and never to say,

oh, well we should be more like it was

4,000 years ago or even 300 years ago.

We're not aiming for some golden age

of, of a bucolic past that didn't

exist a sort of prolapse area in time.

It's about looking forward and

actually saying how can we have, and

farmers have always been dynamic.

Any farmer who wants to freeze

time and and keep doing what's

always been done has, has always

been bark out the wrong tree.

That's not the way farmers

be ha have ever behaved.

They've always wanted to evolve and be

dynamic and agile and move with the times.

Yeah.

And they have to go with the markets.

And I, I, I don't think the job of

any of us is to try and solve all of

the problems everywhere, all at once.

The market is doing that for

us and, and we'll continue to.

Lamb is being less eaten.

Natural wool are being less worn.

And when people want to farm sheep in

a, in a lower yield number as they used

to be, where they would be herded from

pasture to pasture and they would be

moved constantly so that biodiversity

could bounce back in a rotational system

I think that will of course continue.

Probably forever as far as the

human perspective is concerned.

But the intensive type of farming that

we do at the moment where large numbers

of any kind of livestock are pressed

into small areas of space and given

a lot of artificial feed and then end

up actually often being kept inside.

There was a fire a couple years

ago in Texas where 18,000 cows

died in one fire on a farm.

'cause it's not a farm.

It's effectively a giant multi-story

car park filled with cows that

are plugged in for the whole

of their lives into machines.

And then when a fire broke out, there was

no way to unplug these bovine cyborgs.

And they, and they all perished.

And the same thing happens in pig farms

and increasingly in sheep farming as well.

And I just believe that the markets

are going to, not just the markets,

but societal opinion and government

policy are going to start shifting

people to different models of farming.

And as they do that, there is an

opportunity for the resurgence

of our rainforest landscapes.

Rupert Isaacson: Sure.

So, okay, so now I think you actually

answered my question there very well,

which is, some sheep, but not that many.

Which is, so therefore there's more

opportunity to use the, and as we know,

you know, one of the reasons they put

sheep on those marginal areas in the first

place is you can't really use it for Yeah.

Else unless it's trees.

So let's say now that we, we fast forward

30 years and the rainforest, your,

your rainforest trust is the thousand

year trust has kind of done its job

in at least stage one and stage two.

And we are seeing a Cornwall that is

effectively a, a secondary rainforest.

And we mentioned ecotourism.

So every single 250 acre farm is, is each

one going to sort of have its own glamping

site and or are you going to have.

Is it going to go a little bit like those

private game reserves in Africa, where

they operate almost as collectives and

you could safari through, let's say,

you know, I, I stay at Cabilla because

you guys have bison, you know, and

then I walk or I drive over to the next

rainforest farm through a rainforest

path because they are bringing back all

rocks and yeah, wolf, you know, and then

I get to see those and then I go over

to the next one and they have links, you

know, and so therefore I'm on this sort

of safari that you guys ought to some

degree pull the money from, but that

you each have a little small lodge, you

know, on your land, which could operate

at like a camping level or at a luxury

level depending on the, so I'm familiar

with that 'cause my family did safari.

We actually ran a a quite remote lodge

in Zimbabwe for many, many years.

And we did it on these multi budgett.

Thing.

So you'd ne we'd never get turned away.

If you just showed up with a tent,

you could totally camp there really

cheaply, just come up and eat in

the restaurant or eat, you know,

cook your own food, whatever.

If you wanted to come and

spend a lot of money, great, we

could accommodate that as well.

And all of that money just was plowed

back into the elephant conservation

that, that we were doing at the time

and, and keeping the lads employed.

Are you looking at something like that?

Some sort of ecosystem, some sort of

ecotourism, patchwork, which then the, so

the farms are making money from timber.

They're making money from

carbon sequestration.

They're making money in this sort of

patchwork way that people can move

through larger areas in eco safari thing.

And there's reintroduction of sort

of megafauna, you know, what you,

is it looking like that?

What you've described is, is a, is a

very beautiful model for the future.

And, and, and in all honesty, that's not

that, that model that far out is not our

mission right now because that's I think

that's a, that's a, a a wonderful example

of how it might work one day scare.

Yeah, yeah, exactly.

But, but Cornwall and, and a lot

of sort of southwest Wales and the,

the temperate rainforest zone, a

lot of the economy in these areas

is already hospitality focused.

Yeah, that's true.

And tourism focused.

Cornwall has a big problem where

you basically can draw around the

coast of Cornwall with a Sharpie.

And that is the economy at the moment

because everybody goes to the beaches

of Cornwall because that's where they

think of as being the places you go.

We're passionate about drawing people

a little bit more inland to see some

of the beautiful inland Cornwall.

And, and I, and I also think that

there's a really beautiful opportunity

for us to use some of the models

that we see in the global south.

And, and bring them to the global north.

Yeah.

We've had this, this knowledge

transfer and, and the same in the

scientific community for the last few

hundred years where Western developed

in inverted commerce countries are

telling underdeveloped countries

not to cut down their trees, not

to kill all their megaphone, and

not to kill our apex predators long

after we've already all done it.

And I think there's a time for humility

around both nature conservation,

about where we sit back and go,

actually, how is it done in Zimbabwe?

Where, when it is being done really

well, how is it done in Sumatra?

How is it being done in Patagonia?

And learning and listening.

But I think alongside that,

things like ecotourism, we

could learn from that as well.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

So, so Robin and I, I want get, I also

don't want to get off this podcast

without talking about the crazy thing

that you guys are going to do in, but

yeah, we haven't, we haven't thought

about any that We'll get there.

We'll get there.

But Robin Survival International, I.

Was founded really so that we wouldn't

lose indigenous wisdom effectively.

Right.

And you know, I learned, I learned so

much from my, what did I learn from my

time with the Satan, with the Bushman?

It wasn't just about land management.

I learned lots about land management.

I learned lots about

relationship with species.

I also learned about relationship

with the supernatural.

I, I learned about healing technologies.

I learned about spiritual technology.

I, I learned about human happiness.

What I really learned about was parenting.

I observed that these people because

they got so much unconditional love,

like so much in the hunter gatherer

context, because they're not being raised

to be warriors that, so there wasn't

this idea that we gotta toughen you up.

It was the opposite.

It was, let me just try

to fulfill all your needs.

And then you'd see these people at about

16, they'd just kind of take a spear,

go into the bush, come back with the

wildebeest, and then two years later

they'd go off down to Johannesburg,

like go into the city and learn to

speak Zulu, English and Aans in like a

year, just peer over somebody's shoulder

while they're messing with a vehicle.

And within six months they know

how to be a diesel mechanic.

And then come back to the bush

and be to, and I, I realize, oh my

gosh, oh my gosh, that the mental

health of these people is so good.

This is how we're supposed to be.

And it starts with these things like

co-sleeping and wearing your kid

on your body, because you wouldn't

dream of putting your kid on the

other side of the hut because ness

will come into your hut and take

your kid, and you won't even here.

So you, and it goes Sub-Zero at night.

There's no way you, you're

gonna do that, you know?

Just be stupid.

So the, the practicality led to this.

Functionality was also a very

compassionate community because

everything's about problem solving

because you're not the top predator.

So rather than creating conflict,

you had to always resolve conflict.

And for that you had a shaman or

a healer standing at the center of

the community so that when the funky

monkey shit happens in our funky monkey

brains there's some way of sort of

washing the psychic dirty laundry.

And I realized, oh my gosh, oh my gosh.

You know, we, we moved so far from this

and this is why we're all so messed up.

Now, we go to the rainforest, our

temperate rainforest, the Celtic,

you know, Sylvan Lu flutes and chased

me around the red maple, you know,

chaps with pointy ears and so on.

But it still comes outta

the warrior culture.

All of the Celtic myths are about people

being committing acts of atrocity to

each other and basically ripping each

other's guts out and do being horrible.

You know,

do we have a chance?

When it comes to the rewilding of

the land in this way, Robin, you've

been, you've been an advocate

of you're one of my heroes.

You know, because we couldn't have done

what we did in the Kalahari without you.

There's no way you

provided that structure.

You now in an interesting position where

we could rewild our western warrior

culture that juts out into, you know,

the, the British Empire and the piracy

and all of that and the colonization,

and which came on the back of just

the Iron Age warrior culture that came

on the back of the Bronze Age warrior

culture that came on the back of the

agricultural revolution that caused

all the shit in the first place.

And you guys are really at this

cusp of reconnecting with our source

ecologically, but also culturally.

Dream a little.

What, what do you see as the, you know,

I, I do, we have a chance to become

pre Celtic Bushman, like cheddar man.

Being nice to each other rather

than shitty to each other.

And but still keeping our technological

goodies somehow while rewilding back

to what produced us in the first

place before it all went wrong.

Like, what are your thoughts on that?

Robin Hanbury-Tenison: I've always been

a great believer in using the best of

technology as well as the best of natural

living to combine together and get the

best of both worlds as an objective.

And wouldn't it be wonderful if, if

we were able to reforest a proportion

of Britain, yet Nolan knows all the

figure, but I mean, Britain is the

least forested country in Europe.

What is it?

13% and Oh yeah.

13, 14% in the UK can benefit

33% in in Europe, 8.5%

in Cornwall.

Robin Hanbury-Tenison: So if we just

brought ourselves up to the European

average of, of doubling or troubling

as far as the land of Britain, it

would begin to change a lot of the

stuff you're talking about with because

there would be access to that lamb,

which would give people the freedom to

start enjoying the sort of lifestyles

that we all know are healthier.

I mean, both you and I have done

a lot of long distance riding.

Will and I have written eight long

distance rides, a thousand miles or so

around different countries in the world.

And I always say it is the ultimate

way to experience the world because

you are riding on an intelligent animal

and riding from wonderful countryside.

And Britain is very depleted on ride

paths for various historical regions.

And wouldn't it be wonderful if, if,

if one of the ways in which people

began to access the countryside

was on a horse and being able to

have the economy as you touched on,

of the local farms turning from.

Being purely short,

being hospitable as well.

So to do the ride anywhere, in any

direction and end up finding someone

where we could put horse up and stay for

the night and move on through the woods.

And it, it is a glorious way.

We did it in we, we inaugurated pen

I right away, which is right above

it runs now, runs all the way up

the pens in the middle of Brooklyn.

Very poor farming lab for farmers.

Very, very little

opportunity diversification.

And one of the things way back, this was

20, 25 years ago I was banging on about

then was that there's a huge opportunity

for every farm in those remote penan

not so different upland to be able

to be ready to facilitate visitors.

And if they, if it became a standard

thing, it would be, they'd be putting

up different people every night

and charge them a certain amount.

Bombing people effectively.

Yeah.

And local on the Camino

route in northern Spain.

Absolutely.

Exactly.

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: No,

I'm, I'm, I'm with you.

You've actually just

described Hessen where I live.

I can ride, I can get on my horse

and if I see it, I can ride it.

It's, it's, I've never

experienced this anywhere else.

There's this crazy tolerance here.

It's also not a fence landscape.

It's not really a livestock

area, so it's either orchards

cropland or hay meadow or forest.

Right.

Go ahead.

Yeah, Melin.

I just, I just, because everything that

you just said about your experiences

with the San and I, I say that I have a

2-year-old and a 4-year-old at the moment.