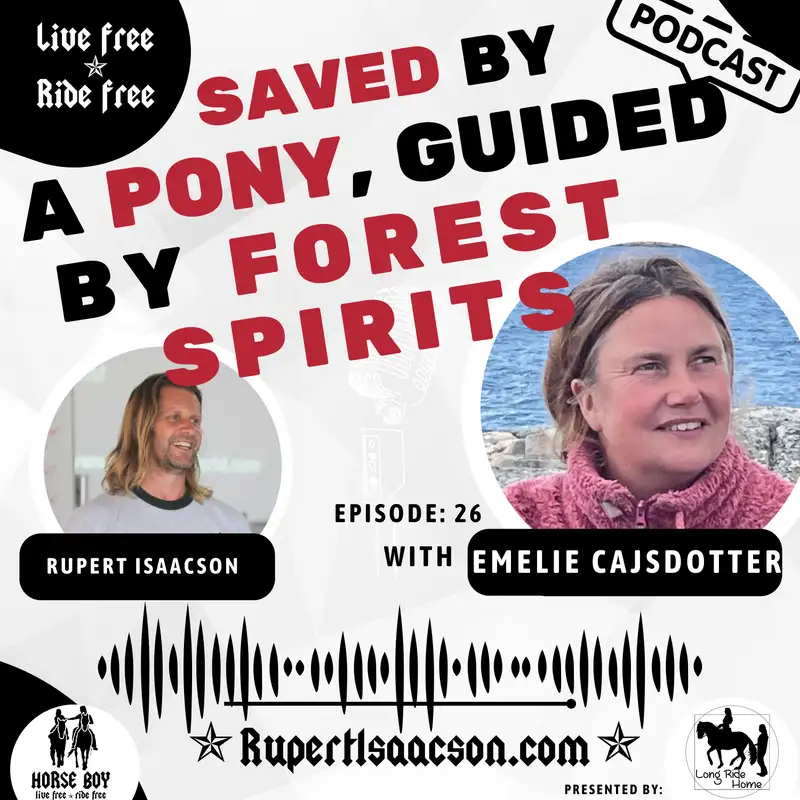

Talking to Stones, Ponies, and the Sacred: Empathic Interbeing with Emelie Cajsdotter | Ep 26 Live Free Ride Free

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

, people, this is an interesting,

, and rather exceptional

podcast we have coming up.

I just want to give a disclaimer.

There will be some

potential triggers in here.

We'll be talking about, , suicide,

suicidal ideation, and also some

aspects of the supernatural.

So if any of these three

things are trigger points for

you, please switch off now.

Thanks for joining us.

Welcome to Live Free, Ride Free.

I'm your host, Rupert Isaacson, New

York Times bestselling author of

The Horseboy and The Long Ride Home.

Before I jump in with today's guest, I

want to say a huge thank you to you, our

audience, for helping to make this happen.

I have a request.

If you like what we do here,

please give it a thumbs up,

like, subscribe, tell a friend.

It really, really helps

us to make the pro.

To find out about our certification

courses, online video libraries,

books, and other courses,

please go to rupertisakson.

com.

So now let's jump in.

Welcome back to Live Free, ride

Free, where we talk to people

who have lived and are living

self-actualized lives of all kinds.

And what can we learn from them?

Today, Emily K's daughter

you're gonna think I'm nuts.

Emily doesn't just talk to animals.

She talks to the stones, the

mountains, the trees, the lot.

And those of you who know me will know

that I'm actually quite skeptical of

this because in the work that I do with

horses and with autism, I get a lot of

people coming and saying, oh, I'm an

animal communicator and blah, blah, blah.

And usually my bullshit meter

goes, beep, beep, beep, beep, beep.

And the reason it does that is because

frequently the reports of what the animals

are saying or whatever is often somehow

negative towards the humans or something.

And I, in my time with the Bushman

the sun in the Kalahari where

there's a lot of direct animal

communication going on, those kinds

of things are never the message.

They're always much more within

the animals sphere of reference

of which we are peripheral, not.

Central.

And so this idea that, well, you know,

my rider doesn't ride me well enough, or

something like that, just always struck

me as sort of one human to another human,

sort of using the horse as a, you know,

way to criticize another human basically.

But the fact is that communication with

nature is a real thing and has been a real

thing ever since humanity has been here.

Because guess what?

We're part of nature.

And if you've spent any time with

hunting and gathering people, some of

you listening have, you will know that

the way in which they communicate with

the environment around them, anima

and inanimate is appears supernatural.

However they would posit and I

think I would posit having spent

a lot of time with them, that it's

not supernatural, it's natural,

it's just that it's happening on a

level that we have forgotten, lost

the need for, become deaf to, et

cetera in post agricultural society.

So anyway, that was a long preamble

to say that Emily is one of the

few people I've met who seems

to have an unbroken connection.

Despite being within our society.

And I find this fascinating and I

want her to talk to us about it.

So, and, and how really this

has defined her life and, and

her livelihood and everything.

So, Emily, welcome.

I hope I did you justice.

Tell us who you are, what you do.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Thank

you for having me here.

And as you and I know but maybe the

listeners do not, is that you helped me

a great deal by, by saying that, this

way of relating to your surroundings

which I have recently just given the

concept name empathic inter being that

that is a natural state for human being.

So maybe I'm not the weirdo after all.

And that was both very devastating

for my ego and helpful for myself.

Rupert Isaacson: Oh, sorry.

I'll try to stroke your ego.

No, no.

We inate of course.

No,

Emelie Cajsdotter: once we got it crashed,

please don't put it together again.

Yes, it's, it's hard

to know where to begin.

An answer to that question.

Start,

Rupert Isaacson: start at the beginning.

Okay.

You, I forgot to say

that you're in Sweden.

You are in a very natural

place in, in Western Sweden.

But take us back to your beginning

because I know that you were not always

raised in nature that no, not at all.

How did this evolve for you

to start as a small girl?

And just take us on the journey, please.

Emelie Cajsdotter: I think when

people see the work I do today, which

is living in nature, working with

biodiversity, communicating with all

sorts of living entities it's easy to

think that I grew up in the countryside

in very sort of loving and caring

environment, but it was the opposite.

I don't mean to blame anyone by saying

that it wasn't loving and caring.

It, it was a, a great

destructive mess as I think why,

Rupert Isaacson: why

Emelie Cajsdotter: or

civilization in many places are.

My father I grew up in a highrise building

in the outskirts of Gothenburg in Sweden.

One of these high rise building with

sort of 10 floors and several doors in.

And I had a key around my

neck because, there weren't

really very many adults around.

And it was this sort of concrete

jungle type environment.

And my father, who most likely today

would have been given some sort of

diagnosis within the autistic spectrum,

was a researcher in abstract mathematics.

And that he could do, he

was apparently very, very

intelligent in that narrow field.

And he lived his life

on that very fine line.

That fine line.

Didn't include any social skills

any capacity to at all interact

with his surroundings including me.

And he died when I was five in

what was most likely suicide.

He had asthma and he mixed his asthma

medicines so that he suffocated and died.

And I was five at the time, and I

was with him when that happened.

So I would say that that had a

huge impact on me and still do.

It's like there are things that you sort

of get over and that there are things

that you learn to integrate in your being.

And I would say that that

would be one of those.

Rupert Isaacson: Does that mean

you actually watched him die?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes, I watched him die.

Rupert Isaacson: Can please, if it's

all right, take us through that, because

Emelie Cajsdotter: yeah,

Rupert Isaacson: that

could mean so many things.

Can you, can you be as

clear as you can be?

What, what happened?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

Well, I was five and people think,

tend to think that children are

very unaware of what happens around

them, especially in a younger age.

And I have very clear memories from

a very young age, and maybe because

those are my links to my ancestral

memories and maybe I, my being would

be more alert to really collect them

somehow knowing that he would pass.

This was not the only complication.

My mother was not really equipped

for the role of having children.

And she knew that she knew that that was,

this was really not at all doable for

her for various reasons, but she grew

up in a, in a generation where having

a husband and children is what you do.

So.

It, it was what it was.

She couldn't really at all

deal with having children.

So, and since my father was also

incapable of any kind of care it was

my mother's mother, that grandmother

that would basically raise me.

And she was a psychic healer.

So thi this is the,

this is the little pool.

Rupert Isaacson: Just quickly,

you were an only child?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

I think maybe, I mean, as much inspiration

I got from this upbringing, I, it

might also be a good thing that there

weren't a lot of kids in this situation.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

And then the second

thing, this grandmother.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Your mother's mother.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: Also in

the tower block there in

Emelie Cajsdotter: yeah, in

another highrise building.

Actually, not in the beginning, but

after my father died and she realized

that this is all gonna go to pot she

moved to another highrise building.

Where, where was she

Rupert Isaacson: before that?

Was she more in the country or, or No,

Emelie Cajsdotter: she was in

the middle of the city as well.

Her interesting dream was always

to become a mathematician.

She was also highly intelligent

in that measurable way that

makes sense for mathematics, if

Rupert Isaacson: well, all

these people working for Saab.

I know that Gotham, no,

Emelie Cajsdotter: none

of none of them were

Rupert Isaacson: center for the Saab.

Emelie Cajsdotter: My father was

working in the university and my

mother was working in the university

too, because she has this whatever

unusual skill with languages.

So she speaks seven languages.

And your mother?

Yes.

They all have like racing heads.

Rupert Isaacson: Is your

mother still around?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Okay.

And so, so did my grandmother,

but my grandmother being born

sort of, well more than a hundred

years ago she was never allowed to

pursue in any studies of that kind.

Rupert Isaacson: And when you say

she was a psychic healer, sorry,

I'm, there's a journalist in me.

I've gotta piece all puzzle

pieces together first before we.

Psychic Keila.

How did you know?

How did she know?

And in that urban context, that's million

Emelie Cajsdotter: dollar question.

She was very good at looking into

people's future, and I didn't

really like that because she

Rupert Isaacson: would

do that as a party trick.

She'd do that for a living.

No, no, no.

People came

Emelie Cajsdotter: to ask her for

help and she never charged money.

She had some other daily,

Rupert Isaacson: but how did that evolve?

How did it evolve that, did she go

around saying, oh, and by the way,

you, oh no, people just, you're gonna

blow your nose next Tuesday week.

Or like, how did people

find out and how did, I

Emelie Cajsdotter: don't know because I

was so young, but they just, they just

knew and they just, and people would were

Rupert Isaacson: around coming to her.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

They would come to her.

And I, they never

Rupert Isaacson: asked.

She never told how it evolved.

Emelie Cajsdotter: No, actually

I never really thought of it

until you ask now, to be honest.

Anyway.

She would very good at, at

that's, that's brilliant.

No, she would see people's future.

And I found that a bit uncomfortable

because it, it raised the question

in me whether there actually

is a, a set destiny or not.

And I didn't really like that.

Mm.

So I didn't want her to

see anything about me.

Some, she said a few things anyway,

because she just couldn't stop herself.

And, and so far she's been correct.

But she also believed in all

sorts of guardian, angels,

reincarnation all of these things.

Rupert Isaacson: Do you know

how she evolved these beliefs?

Emelie Cajsdotter: No.

Okay.

Rupert Isaacson: Because it doesn't

sound like it was in the family culture.

The family culture was very

cerebral and very intellectual.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

I have no idea where that comes from.

Was she religious?

Interesting thing is that on my

father's side his sister has almost

the same qualities and nobody

knows where that comes from either.

Okay.

So

Rupert Isaacson: strange northern people.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

Yes.

And she was such a good healer that if

I was at home and she was at home and I

had a headache because I had migraines

for as long as I can remember, and

I would have a migraine coming on, I

would call her and she would just do

something that I wouldn't know over

the phone and the headache would go.

And, and to me that was always normal and.

And when I started to have experiences

myself and, and, and being confused and

scared and overwhelmed, I would tell her

logically she would be the one to tell.

And she would always

tell me that it's normal.

She never made a big deal out of it.

She never made me feel special,

and she never made me feel wrong.

So, thinking about it afterwards,

I think that approach of this

is fine, this is normal was very

helpful in whatever happened later.

Rupert Isaacson: And she never, she

never asked, told you, or you never

asked, where does this come from, granny?

You know how No.

Okay.

Okay.

There.

No, it just felt

Emelie Cajsdotter: natural and normal.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And before my

father died he went to her and asked

her if she could look after me.

And she saw him dying.

She told me that years later she saw

him dying and didn't want to believe it.

Mm-hmm.

So, but she didn't want to upset him,

so she said, yes, of course I will.

And then he died.

So, she would be my sort of human

contact, but she, I think she taught

me so many things, and maybe one

of the most important things she

taught me, because she later ended up

committing suicide as well, but then

I was 17 years old is that there is

nothing black and white in this life.

Mm-hmm.

It's not that.

How could she teach me all the things

that has proven to be so helpful

throughout my life and still not

being able to live with herself?

How, how is that possible?

And, and how can my father who I felt

some strange bond to, although he

could never show emotions in the usual

way, he could definitely radiate love.

How could he kill himself?

And I come to this soothing

free conclusion after

dealing with this for years.

Is that because all of it is

possible at the same time?

It's, yes.

My grandmother could teach me

all these things and she still

couldn't live with herself.

And both are true.

And although they are completely

contradictory they can definitely

coexist within the same human being.

And it doesn't affect my love

for her or for any other of my

highly destructive family members.

Rupert Isaacson: Let's just go back

to, I, I want to delve into, in, in

a moment what we think the motives.

'cause I suspect the motives for

each of them to take their own lives

were probably a little different.

And I think this is a, a worthwhile topic

to explore for the reasons that you just

mentioned, and that many things can exist

simultaneously, including timelines.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

You

Rupert Isaacson: know, having,

again, spent a lot of time

with indigenous people.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

And I think for, sorry, for a modern,

civilized human being you could say

that this was a harsh learning curve.

Rupert Isaacson: Yes,

Emelie Cajsdotter: for sure.

But maybe a small chart

Rupert Isaacson: because, you know,

you also rely on your parents to

Emelie Cajsdotter: but maybe that's what

it takes to break down this linear mind.

Rupert Isaacson: Right, right.

And linear, I think is the word there,

because if one thinks of time as, as

vertical, which indigenous people tend

to that, as far as I've been aware,

then as you say, things are happening

simultaneously, past, present, and future.

We think of it obviously

very much as linear.

And are brought up to think that way.

And of course it's comforting.

I feel more to, and I'm all about comfort.

I think comfort is good to

think of it as vertical.

But let's just go back to, I just want

to now dial us back to your father.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

Yes, please.

Rupert Isaacson: You are you, you

said, you say you, were you in

the room with him when he died?

Like, did you see him die?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Well, I saw him

almost die which also is a storyline.

He had taken those medications, he

mixed his medications, and later I

was told that he'd mixed them several

times before and ended up in hospital.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Emelie Cajsdotter: So I

understand that he, to some

extent, knew what he was doing.

And this was between

Christmas and New Year's.

And I remember that Christmas, I was

clinging onto him in a way that I would

never do because, because he wasn't

physically accessible as a father.

You couldn't sit on his lap.

You couldn't hug him.

He didn't, that, that's not

how you interacted with him.

But and, and for me, that was fine.

But on that Christmas, I remember like

really grasping him, like holding on.

Legs and arms and clothes and whatever.

So, so somehow I knew and, and,

and he knew that, that there,

there is a parting coming.

And when it actually happened, he

was sitting on the bed in the bedroom

looking out through the window.

And outside of these windows in

this flat, we were on the third

floor, were this amazing old tool.

Although we were in the city beach

trees, like huge, very dark stamps.

And, and it took me many years to

fully understand how present they were.

It's like, yeah, you think

you're alone and, and you're

vulnerable and very exposed.

You are when you're a kid and

everything is falling apart.

But those trees, they were there

and they helped much more than,

than I was aware of at the time.

So they were also there.

So he's looking out of the window at

the trees and so am I, he's not looking

at me, we're not having any contact.

And I understand that he can't

breathe and he's about to fall,

so he collapses on the floor.

So I see him collapse on the

floor and I think that he is

still in his body as that happens.

And sometime around that time, the

neighbors comes and they take me out

and they, and they say that, oh, he's,

he, he only has difficulty swallowing.

I know that he's dying.

But I think the fact that I, at that

point in time didn't see his spirit

leaving left me in a state of something

that later turned into quite an extreme

workaholic personality where I spent

many years trying to save and rescue, I

dunno how many individuals and animals,

mainly, I mean, we have a sanctuary here.

And I'm not saying that that's

wrong, but in adult years I

understood that within me.

He wasn't really fully dead.

It took me years to accept that he was.

So, every time I got a chance to

save someone, there was hope for him.

And every time I couldn't, I

had to face this bottomless pain

of accepting that he's gone.

So you could say that that

story went on past that point.

Although after his death, quite shortly

after, I could see him sitting in the

living room, always in the yellow pajamas.

I have no idea why he would

always have those clothes on.

But and, and I could talk to him

and I realized that he is dead.

But he's visible to me sometimes.

I can't control it.

I can't ask him to come.

But sometimes he comes.

And you mentioned the reason for

him choosing to die, and, and I

think he answered that in, in one

of those early meeting points.

Then I went on into my

own self-destructiveness.

So

Rupert Isaacson: you can't go on,

you just gotta tell us what that is.

You can't drop that and leave it.

No,

Emelie Cajsdotter: no, no, no.

I'm gonna go.

Okay.

But what, what he said is

that the difference between

you and me is the words.

And what I understand from

that sentence is that.

Yes.

I also live a life that is

quite a thin thread that goes

far out from what's normal.

But I have a way to reconnect to

the common world of fellow human

beings, which is through the words.

And he didn't he left a box of

equations that no one could solve.

He never expressed himself

except that one time after death.

Rupert Isaacson: Do you think he left

because he found it to painful to be here?

Do you think he left because

he felt he could do his work

better from another place?

Do you think it was an act of, was it

an act of distress, him taking his life?

Or was it an act of

logical creativity to sort of go to the

next professional phase or something?

What, what, what, what do you

Emelie Cajsdotter: I always felt

it was more on the desperate side.

Okay.

Rupert Isaacson: What, what was it

that he found so painful, do you think?

Because if he had the job in the

university and he could exist

in that mathematical world.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

You know, he had to, and then

Emelie Cajsdotter: he had been

offered a job at Stanford University

too, so he could have gone deeper.

Mm-hmm.

And probably met more people

that wouldn't find him so odd.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Emelie Cajsdotter: But he, he chose

not to which is unexplainable.

But I think what I continue to

explore after this and still do,

is the isolation of modern humans.

Mm-hmm.

I think there is a specific pain in

isolation that may not be like emotional

heartbreak, the type of pain or anxiety,

pain or those things that we can phrase,

but another overwhelming pain that is both

inside and outside and might be the reason

why we feed ourselves so much stimuli

and why we are so costly for this planet.

And I, I think for him that isolation

was, very obvious and maybe the things

that more so-called normal people would

do to suit that pain didn't work for him.

Rupert Isaacson: Do you think in

another, perhaps more authentic human

context he'd have been All right.

And if so, what would that context

have been and what would his

role have been, do you think?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Well, I think

when I live with animals, any

other species, I notice that when

you remove the filter of linear

thinking, you also remove hierarchy.

And when you remove hierarchy based

on values everyone seemed to have a

unique role that is unmeasurable in

value and uncomparable with anyone else.

And what I also notice is an

obvious acceptance that you're

not meant to be anything else

that would be stupid to be honest.

So it seems like everyone else

except the modern human, linear

society is making maximum use of.

Individual capacity one way or another

which means that you don't have to

do things that you're not meant to or

that you're not cut out to be able to.

Which means that if he lived in,

in a, in a herd of horses, he could

probably have spent his whole life

diving into this far, far, far

away place of abstract mathematics.

And someone else would make sure that

the wolves don't eat him or that they

do get to the water place and that he

does get to sleep sometimes thinks that

he could never really do for himself

as a human being would maybe in a

different society be okay because it

would fit somebody else's unique role,

Rupert Isaacson: I guess.

Right.

My question there though is that he

was, he was clearly valued, right?

He had a job at the university

so people saw the value of

his mathematical brilliance.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

But I think it's in the relate, in the,

in the possibility to relate to others.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Right.

So the, the professional context

not being enough, even if you're

surrounded by your fellow nerds.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

Yes.

And, and, and if you look at

so I think we've all along been

looking for the same thing, but my

approach is completely different.

I think when,

when I would try to explain any of

what empathic, inter being would be.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm.

Emelie Cajsdotter: It's not, it's

not being psychic, it's not reading

something, it's not interpreting someone.

It is for a moment fully with

all senses, experience the

other one's reality from within.

And that can only happen if I am available

to the same extent for the other one.

Rupert Isaacson: So feeling gotten

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Feeling seen.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

So I exist in you and you exist

in me, and I think that is

probably our original context.

Mm.

And when we lose that.

We begin to experience some

sort of alienation that is

harder for some than others.

But I would say that a lot of

states of being that is normal

in, in modern human life is maybe

a symptom of lack of empathic

inter being and not normal at all.

I I, I've heard you talk sometimes

and you seem to often mention

that joy is a natural state.

I would agree.

And so what every other

species that I've met so far.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: So why

do we have so little joy?

And, and, and why does it disappear

in such an early, why do we stop

playing earlier and earlier?

We do.

Rupert Isaacson: I think, I think we're

told to, I think we're conditioned.

Yeah.

But in our, in our natural

state, I don't think we do.

Emelie Cajsdotter: No.

So, so there are lots of things that we

take for granted as a normal maturing of

a human being that might not be at all.

Rupert Isaacson: Absolutely.

Yeah.

There's, well, I put away childish things.

I'm like, fuck that.

I mean, really, honestly I'm just

thinking as, you know, I'm, I'm

just imagining, I'm projecting in my

imagination your father as being, say

in the Kalahari or, you know, east

Africa or Paleolithic, even Neolithic

Europe, you know, and I'm imagining him.

Organizing the construction

of a stone circle

Emelie Cajsdotter: Exactly that, you know,

Rupert Isaacson: and so those are my

questions, you know, it's like, okay,

who built those ancient observatories

that now we realize go back way

further than we thought they did?

You know, with the new findings that

Gobekli Tepi and earlier archeological

things that are, that are now rewriting

the whole human history thing from when

I was an archeologist and historian

at university, which is, you know,

starts with the Sumer 6,000 years ago.

It's mm-hmm.

You know, Goli, Tepi, they now know is

6,000 years older than that, and they

just found another one close and there's

this new one in Indonesia that's older

and these were being organized by people.

And you could say, well, yeah, he was

doing that at the university in Goberg.

Yeah.

But not in a way, but in

a way that was isolated.

Okay, you must sit here in this

department of mathematics or

this department of physics at the

end of this corridor in a box.

And you, and now do your equations.

Put them in a box.

Yeah, exactly.

Rather than.

Observe the heavens.

Mm-hmm.

Show us how to observe the heavens.

Exactly.

Be our mad, beautiful

druid who emanates love.

Yes, we will absolutely make sure

that there's venison for you because

we need to understand why that

strange light in the sky is coming.

We need you to make those

calculations for us please.

And we realize that that's gonna

take you, you know, five months of

just sort of more or less sitting in

your heart while we bring you things

and we are going to work on healing

you and we are going to love you.

Exactly.

And let you be.

Emelie Cajsdotter: That would've

worked is my, that would've

Rupert Isaacson: worked.

Yeah.

Yeah, yeah.

No, I get it.

I get it.

I get it.

Because, you know, he must have

had a great joy like I could

imagine when he was in flow and

he was in the zone with his Oh,

Emelie Cajsdotter: yes.

When he was flow, flow, he would

gallop around in the living room

and jump up and down and make little

noises which was hilarious to watch.

Okay.

So he, he did express himself,

but not, not the way you would

expect an adult man of his age to.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

So he was playing among the

fractals and the fib sequence

and the beauty of creation.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: But unable to

Emelie Cajsdotter: gallop

on the spot like a horse.

Fantastic.

Something

Rupert Isaacson: autistic behaviors.

Yeah.

No, a, a amazing.

Okay.

Okay.

So he leaves.

Mm-hmm.

You are there when that happens.

You are five.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Let's go on from there.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Well, the thing

is you might think, think that lots

of things happened after, but I would

say that a lot of things also happened

before, and, and I know that they

happened before because this is such a

cut in my timeline, so I know how old

I am depending on if he's alive or not.

So I know that before the age

of five I have this obsessive, I

would call it obsessive fascination

with the end of consciousness.

So my thought that I can't let go

of to the point of having panic

attacks and not being able to sleep

is is the universe expanding or not?

This is what I think about constantly.

But I can't really phrase

it because I'm too young.

But this is, this is on.

Why

Rupert Isaacson: would

that have mattered to you?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Well, I have no idea.

But it did, I mean, it was

a matter of life and death.

I could not stop thinking about it.

And, and I still find it fascinating.

Rupert Isaacson: Did you ask your dad, did

you ask those adults around you because

they seem to have been the people who

would've also thought of such questions?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

Maybe we did, did discuss some of it.

I don't know.

But what I do remember is this

constant thought and finally

coming to the conclusion that

maybe the universe is expanding.

I think I came to that conclusion

because that was the easier for my mind.

So I.

If it was expanding, it would have an

edge because otherwise there wouldn't be

a sort of something that would expand.

Expand.

And if you come to the edge, if you come

to the edge, how can you get past the

edge and remain aware of that happening?

How can you cross the boundary into what

is non-existent and still exist beyond it?

And then I, I would go to that

point and then I would sit and tell

myself the word eternity, eternity,

eternity, until I got so dizzy and,

and would hyperventilate and panic.

And then I, and then I had this

pile of Donald Duck magazines.

'cause I learned to read

when I was really young.

Sort of, I remember sort of instant.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah,

Emelie Cajsdotter: yeah, yeah.

And, and I would turn on the light,

look at Donald Duck for some reason.

Donald Duck.

My mind would calm down and, and, and

understand exactly what I was looking at.

Then I would close the lamp and

I would start all over again.

And I would've nightmares

and, and, and scream and cry.

And, but I could not, I was

so drawn to, to that Okay.

Sort of far end of the, of, of what

was still accessible to my mind.

Rupert Isaacson: Hmm.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And I still is yes,

I'm still extremely fascinated of what

happens when we expand ourselves beyond

what is possible for the, for the mind.

I st I still find that very fascinating,

but maybe not to this or maybe

I still do get anxiety from it.

I don't know actually, but

I did when I was young.

So that was before he died.

You would think that you would have all

these existential thoughts because you

experience death, but that started before.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

So you are dealing with the idea of the

limits of consciousness very, very young.

Then your father does die.

Yeah.

Can you take us through the rest

of your childhood now go into

your childhood, into adolescence.

Take us on that journey.

Emelie Cajsdotter: After my

father died, I, I had a real fear.

I mean.

Existential anxiety is something

because you choose it somehow.

But this was real fear because I knew

that I was left with my mother, whom

I was terrified of because she really

had these temper tantrums and fits

that was completely unpredictable.

Okay.

So I was really really afraid of

being home, of going home alone.

And because I grew up in this neighborhood

where it was this sort of high rise

buildings is usually for people who

for some reason don't have a lot

of money or they have other issues.

So there would be quite a lot

of alcoholics and drug addicts

and other broken families.

Even

Rupert Isaacson: though your dad had a

good job at the university and so on.

Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Could he have

afforded something different or,

Emelie Cajsdotter: I don't know.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Interesting questions

Rupert Isaacson: because yeah.

You associate university professors with

living in nicer neighborhoods and things

Emelie Cajsdotter: like that.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah, yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

That was never explained to you?

Emelie Cajsdotter: No.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

But okay.

You're in a slightly

depressed neighborhood and

Emelie Cajsdotter: yes.

Which means that there are lots

of other kids with broken homes.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And we find each other

and form some sort of family of our own.

So, that I would say was quite helpful.

Okay.

And I could explain to them that

I don't dare to go home by myself.

My mother threatened to kill herself and

because to me that was a real threat.

It could happen.

Yeah.

I didn't want to find her dead, so I

made sure I always had a friend coming

with me if I was going home after school.

Okay.

And from the age of seven, I

started to ride in a riding school.

Rupert Isaacson: Why, how did that happen?

Emelie Cajsdotter: I just

wanted to be near animals.

I always wanted to be

near animals, but my why

Rupert Isaacson: riding?

Why ponies?

Why horses?

Why not dogs?

Emelie Cajsdotter: I didn't

really care about riding.

It was just a pool.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

And who organized that for you?

Emelie Cajsdotter: I think

it was my grandmother.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Emelie Cajsdotter: She was behind

a lot of those sort of doesn't,

Rupert Isaacson: yeah.

It doesn't sound like a decision

your mom would've made at that

Emelie Cajsdotter: point.

No.

No.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And because

we're in the city and the stable

is in the city, so I cycle there.

So I cycle to the stable almost every day.

And I'm with a friend in another high

rise building and her mother is working

as a, she doesn't know who her father is.

So she lives alone with her mother.

And her mother is a waitress in a bar that

at that time started to have drag shows.

And this was new in the time.

Right.

And I, I still love drag shows after this.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

How can you not?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

Rupert Isaacson: He doesn't

love a good drag show.

Much of

Emelie Cajsdotter: everything, right?

Yeah,

Rupert Isaacson: yeah, yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: But anyway, joy.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

As you know, if you followed any of

my work, I'm an autism dad and we have

a whole career before this podcast in

helping people with neurodivergence,

either who are professionals in the field.

Are you a therapist?

Are you a caregiver?

Are you a parent?

Or are you somebody with neurodivergence?

When my son, Rowan, was

diagnosed with autism in 2004,

I really didn't know what to do.

So I reached out for mentorship, and

I found it through an amazing adult

autistic woman who's very famous, Dr.

Temple Grandin.

And she told me what to do.

And it's been working so

amazingly for the last 20 years.

That not only is my son basically

independent, but we've helped

countless, countless thousands

of others reach the same goal.

Working in schools, working at

home, working in therapy settings.

If you would like to learn this

cutting edge, neuroscience backed

approach, it's called Movement Method.

You can learn it online, you

can learn it very, very simply.

It's almost laughably simple.

The important thing is to begin.

Let yourself be mentored as I was by Dr.

Grandin and see what results can follow.

Go to this website, newtrailslearning.

com Sign up as a gold member.

Take the online movement method course.

It's in 40 countries.

Let us know how it goes for you.

We really want to know.

We really want to help people like

me, people like you, out there

live their best life, to live

free, ride free, see what happens.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Since I couldn't

really go home most of the time

and she didn't have a father and

she was working nights, um mm-hmm.

My friend's mother would take both my

friend and me with her to her work.

Ah.

So we would hide behind this huge velvet,

courteous and look at these big guys when

they were putting on loose tits and Yeah.

Makeup and glittery dresses and yeah.

I, I, I love that.

I still love the feeling of

sort of, because we knew that we

were a bit too young to be there

Rupert Isaacson:

shapeshifting and role play.

Yes.

Interesting.

Yes, yes.

That shamanic process of transformation.

Yes.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And I loved it.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And there was some,

there was something in there and they

were happy and they were friendly and

and sort of courageous in their own way.

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson:

Non-judgmental, absolutely.

Supportive of each other.

It

Emelie Cajsdotter: was amazing.

I didn't know that that world existed.

Rupert Isaacson: How old

are you now at this point?

Emelie Cajsdotter: I'm probably

like 7, 8, 9 years old.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Emelie Cajsdotter: That sort of thing.

Rupert Isaacson: And you, you

found you're cycling to a.

When you're not going to drag

shows and at school you are, you're

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

Drag shows or, and writing school

Rupert Isaacson: brings, brings

drag hunting the idea of drag.

Yeah.

Yeah.

And when you are exposed to the ponies

at this point, are you talking to them?

Are they talking to you?

Or does this come later?

Well,

Emelie Cajsdotter: this, this

begins this begins I to begin.

Do you

Rupert Isaacson: remember the first time?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes, definitely.

Please,

Rupert Isaacson: please tell us.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

This is a riding school that

is an image of civilization.

This is in the middle of the city.

All the horses are tied up in stalls.

There are almost no fields.

They're in a very traditional regime.

This riding school has changed now to

something totally different, but back

then a regime that is based on obedience.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Like you do as you're

told, or you will be sold or killed.

Yeah.

And, and the horses that come naturally,

they come to this riding school with

quite a lot of energy or vital force,

although a lot of them come through

horse tradesmen and they've had a

troublesome past before they end.

Well, you know how it is.

Rupert Isaacson: I do.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And then they

get broken down quite quickly.

You, you see how they

start with this natural.

Playfulness taking initiative,

making contact, all of these things.

And you see that fall off them as

they stay on this writing school.

And then eventually they will develop

some sort of physical lameness or

other issue, or they will become really

aggressive and then they're gone.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: This

was, this was the situation.

And so one day this pony comes to this

writing school and she's small pony, a

chestnut mare, really, really aggressive.

And in the world of linear

hierarchy it's very important.

Who's the boss?

The whole idea is about that.

So a horse that makes you frightened

needs to know whose boss basically,

so to deal with her aggression,

she's met with more aggression.

Sure.

And usually that will

make one part give up.

And usually that part is the horse

because they have a very bad starting

point because they were slave in

the slave trade to begin with.

So, but this pony doesn't give up.

She attacks back and

she really attacks back.

And if people keep beating her to the

point that she's not attacking back

anymore, she just freezes and waits.

She never submits, she never

shows any sign of submission.

So then people start to, and this

is the writing school teachers, they

start to try to give her sweetss.

This is around the time when, when

horses were given sugar cubes.

So they would put out their hands and

give her sugar cubes and she would

bite the hand, refuse the sugar cube,

making a statement of that and leaving.

So this horse begins

to really fascinate me.

Because for me, yes, I do have a

good time at the drag shows and

I love being with my friends, but

inside this, I am, I am breaking,

because I'm terrified of my mother.

I'm terrified of being home.

I feel no sense of value whatsoever.

I have this unnameable grief over my

father that I can't understand or phrase.

I anyway have all these existential

thoughts that can't stop

because my mind is racing just

like on all my ancestry lines.

So it's very hard to be me.

So

I'm beginning to, I would

say, lose myself at this time.

Mm-hmm.

And I also begin to feel that

may be dying is the only way out.

'cause I know that dying is a way out.

It's present.

Yeah,

Rupert Isaacson: you've observed it.

Yeah.

Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: So, and

I'm not really afraid of that.

As much as I have no bloody clue

how to live in this society.

So when I see this pony who

obviously is impossible to break

down, it makes me very curious.

What, what is her strength?

What is her motivation?

Why, why is she, because for

most of us, it's like the lack

of punishment becomes the reward.

Is that Sure.

Is she all

Rupert Isaacson: right

with a child on her back?

Like it does she, that's

Emelie Cajsdotter: what

throw She throws them off.

Rupert Isaacson: She throws them off.

Okay.

So, and 'cause that was gonna be my

question too, about some of these ponies

that come, okay, they're not having a nice

time in the writing school, but do they.

Enjoy to some degree the relationship

with the children that come.

Emelie Cajsdotter: I'm sure some do.

Mm-hmm.

I mean, some horses that I meet in riding

schools now and, and I definitely would

say that there are riding schools doing

a fabulous job of merging these worlds.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And when I meet riding

school horses that are really content

in the setting, they're in, I would

say they always describe that they have

this group of students that they really

relate to and they feel that they totally

matter in how these individuals evolve.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

Would be very similar.

Exactly.

They're generous.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

They're generous.

Okay.

Rupert Isaacson: But this is

not the case with this pony.

Emelie Cajsdotter: No.

And this is not the case, the way

that place is being run at that time.

Rupert Isaacson: So you become

fascinated with this pony.

What Then

Emelie Cajsdotter: I become

fascinated because what is it that

she has that nobody else have?

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Emelie Cajsdotter: How, how,

why is she not breaking down and

how can she be so courageous?

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Mm-hmm.

' Emelie Cajsdotter: cause she knows that

she's going to be bitten and treated

horribly, but somehow for her, it's

worth it rather than losing herself.

Mm-hmm.

So.

Why does she like picks this, this fight?

Mm-hmm.

So I go down to her stable

and I don't dare to go in

because they're tied in stalls.

And what she does is that she looks at

these people with her ears forward, and

then when they go in, she kicks them

into the wall and don't let them out.

And sometimes she bites people's

stomachs and she don't let go.

And, and I've seen that happen

and they sort of scream and many

people have to go in and take them

out and it's quite terrifying.

So I don't dare to go in, but I'm

totally fascinated and I think that

this original genuine fascination

without an agenda might be one of

the keys to what's gonna happen next.

Because basically my question

to her is, who are you?

It's not, can you please change?

Why are you doing this?

Why can't you behave?

It's who I really want to know who she is.

And now when the horse is here

years later, have started a school

in empathic into being for humans,

this is the question that we work

with the most, the curiosity to

really meet the essence of another

living, being without any other want.

Not because I want something of

you, not because I want it to lead

to anywhere, just because I want.

To be where, where you are somehow.

So this is what I feel when I

stand outside of her stable.

And then something happens

that I would say is grace.

And, and maybe because I

was so ready to give up.

I mean, I wanted to die anyway, so

I don't really have a lot to lose

in having my image of the world

torn down as I probably would have

if I was in a really good place.

Because what happens is that this

invisible plexiglass wall that is

usually between each one of us in this

type of society, meaning that I can see

you and I can relate to you, I can hear

what you're saying, and I can to some

extent, through my biological design.

Also I do have mirror neurons.

So if you were sad, I would be sad, but

I wouldn't know what it's like to be you.

It would always be how I feel when

something happens to you and how I

interpret what happens to me when

something happens to you, right?

In this case, this,

this rule is taken off.

So.

Instantly and without any

warning or preparation, I know

exactly how it is to be her.

It doesn't mean that I

forget that I'm also Emily.

I know that I'm standing on the stable

floor and, and observing her, but so

I know what is me and I know what is

her, but all of a sudden I'm in her

and I'm also in her observing me.

So it's like I do feel exactly

how it is to be her, but she also

feels exactly how it is to be me.

And all of these things are

happening simultaneously without

any stress of comprehending

all of that at the same time.

But what I do find, and

I'm 11 at this time.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Emelie Cajsdotter: What is frightening

to me is that all of a sudden, my

entire foundation of how I've built,

my way of looking at reality is gone.

It literally feels like someone

pulls the carpet and you're standing

on a completely different floor.

And what is inside of her is this

intense sadness and feeling of

being completely misunderstood.

And regardless of how high you

scream and how strongly you

express yourself, no one hears you.

It, it, it, it's, it's like

screaming inside of, you know, one

of those little boxes that has is

soundproof so nothing comes out.

And that sense of extreme powerlessness

was really overwhelming to me.

Now, when her feeling of extreme

powerlessness hits me, it hits me in a

spot where I am forced to see myself.

Because if I, if I am completely

experiencing you, I also have to have

this complete honesty in experiencing

me, because now I'm being seen with

the same eyes from, from the other one.

Mm-hmm.

So I'm also faced with my own inner

state unmasked my own desperation

feeling of never fitting in and

not knowing how to live this life.

All of this is coming crashing

in at exactly the same time.

And, and I, I realized what is what

you would think that there is a

emerging, but it isn't because that

will be a projection and this is not

so, and then she has this image of.

A big barn type building.

And I would never know if this building

existed for real or if it is symbolic.

I can't tell.

But there is an image of a

barn and a low wooden door.

I would say that any old Swedish

wooden barn could look a bit like that.

And in this image, she is being forced

to go in through this small narrow

door with some sort of whip or cane,

or there is something long and narrow

and the feeling is to refuse to go

into something that will diminish you.

And, and I'll never forget that

feeling for as long as I live.

I think which answered my question.

Who, who are you?

Why are you so strong?

Well, this is her strength.

She refuses to adapt

herself to a destructive

circumstance, and she never did

Rupert Isaacson: what

happened to her in the end.

Emelie Cajsdotter: What happened to

her in the end was that she got COPD,

which is chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease and was going to be put down.

My grandmother realized that if this pony

dies, maybe so will my granddaughter.

So, okay.

Rupert Isaacson: So you build

a relationship with this pony?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

Yes.

Because after this event, this,

this happened, I don't know

for how long this went on.

Probably not very long in

linear time, is my guess.

Not that anyone on the

outside would notice.

You would just see a girl standing

in a stable and a horse eating hay.

Right.

And it's completely life altering forever.

And, and I realized that there is another

way I realized that there is something,

there is a way outta this isolation.

Rupert Isaacson: You go and

tell your grandmother this,

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

Rupert Isaacson: Immediately.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Not immediately,

I think, but at some point

Rupert Isaacson: soon-ish.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

Rupert Isaacson: Say, Hey granny,

I've had this kind of Yes, yes.

And that

Emelie Cajsdotter: I feel this.

Exactly.

And then she would say, oh,

well that's normal, and continue

with whatever she's doing.

Okay.

Usually what motor?

Okay,

Rupert Isaacson: so, so the, the

horse develops a chronic ailment.

It's heading for a bullet job.

Probably.

Emelie Cajsdotter: I, I become her groom.

You know how it is in writing schools?

Rupert Isaacson: Yes.

Emelie Cajsdotter: I realized that this

pony holds a key and in my Presumably she

Rupert Isaacson: doesn't pin you

against the wall and rip your guts out.

She

Emelie Cajsdotter: does.

She does.

She does.

Yes, she does.

Every

Rupert Isaacson: time.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

Almost.

This, this, this is also an

interesting part and an important part.

Rupert Isaacson: How do you survive?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Lots of bruises.

She, I feel that she holds the key outta

this reality, so I can't let go of her.

I understand that.

What she shows me is that that key

is equally in me as it is in her.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Emelie Cajsdotter: But with my

linear mind, I need her to not

lose myself is my beginning point.

So I clinging on to this pony.

And the way to do that is to be her groom.

She hates being groomed.

Okay.

And I hang onto her like a drowning man

to, you know, this sort of life vest.

And she begins to test me.

And I think that from a linear

perspective, we tend to see

testing as a, as a power game.

Like you test someone until you know

who's boss and then that sorted.

But what if the test is about who are you?

Do you know at all what you're made of?

What if that is the test?

And it's not about power at

all, because if we remove the

hierarchy it's good for everyone.

Like literally everyone on the

planet that I am the sort of utmost

honest, complete version of myself

because that is my gift to this life.

And, and I'm broken and,

and, and I want to die.

And I'm terrified of everything.

And, and I'm not in a good state.

Mm-hmm.

So this pony doesn't want to be groomed.

She doesn't want me to clinging

on for emotional support.

She can't give any of that.

She knows that.

I have to find that in me.

So she brings me to this difficult

test where most people sell their

horses, which is the test of endurance.

It's like, okay, so now you had

a glimpse of what's possible?

Are you prepared to do the work?

So am I trustworthy to her?

Am I trustworthy to myself?

How do I deal with fear?

All of these things.

I go to her stable every day.

She bites and kicks me almost every day.

And after a year and a half and, and I

begin to develop this love for her and I

begin to realize that that sort of love

doesn't need any confirmation whatsoever.

And after a year and a half, she puts her

muscle on my shoulder for two minutes.

And I'll never forget that

either because I didn't.

Go there every day for a year

and a half for her to do that.

She, she never needed to

give me anything back.

And that was extremely helpful.

If, if I didn't go through those years

with her, I would never work with animals

that has PTSD or go through these healing

processes that takes 5, 6, 7, 10 years.

Maybe the first five without

any results that you could see.

Rupert Isaacson: So, okay.

After she puts her muzzle on your,

on your shoulder, what, what happens

then to her, to you, to you both

Emelie Cajsdotter: Quite shortly

after that, she gets sick.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And you could

easily see how a horse would develop

a lung disease in an environment

that is almost only indoors.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah, totally.

I mean, it's, it's a known

thing with overly stable horses.

Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And you could also

maybe add an element of Chinese medicine

into the equation where lung diseases

is considered, in some cases relating

to inherent fear and deep grief.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

Emelie Cajsdotter: So, and what I saw

was also a horse that constantly fought

for her integrity and she preserved that.

Hmm.

But that also means that during

all the time that you do that,

because you're in a war I.

Hmm.

You don't do all these other things.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

That's exhaust.

Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And, and

you don't live your life.

Right.

You don't thrive.

You don't develop your

your qualities and talents.

You don't make friends, you survive.

You do every whatever it takes to

survive, but you emotionally depleted.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And exhausted.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Emelie Cajsdotter: So she's

going to be put down for this.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Emelie Cajsdotter: My grandmother

interferes and buys this horse,

and at this point I'm 14 years old.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Have you been riding her?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

That works.

She's not throwing

Rupert Isaacson: you off?

Emelie Cajsdotter: No,

she's not throwing me off.

She's brilliant.

She runs really fast, you know,

she, she takes the bit and just

takes off and, and I love it.

Rupert Isaacson: So by then,

you guys have worked out a

relationship of riding together too?

Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

That was the sort of

easy part, I would say.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah,

Emelie Cajsdotter: it was.

And she

Rupert Isaacson: was chucking

other people off before, right?

Yes.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes, she was.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Okay.

But by now, she's, she's accepted you

and you guys are cool together to what?

Yes.

Emelie Cajsdotter: We're

even doing dressage together.

We are doing some sort of, you know,

when there is this Christmas or Easter

or whatever, we are doing little

things, you know, doing the quad

Rupert Isaacson: drills

and the display and that.

Okay.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Like these sort of

mirror things when one tiny, because she

was very small, she's doing all these

things and another big horse with the same

color is doing the same thing and Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Part the, yeah, yeah,

Emelie Cajsdotter: yeah.

That's the name.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay, cool.

So you guys work out

some harmonious mm-hmm.

We do.

Relationship that she carries

you, she agrees to carry you.

Yep.

Then she gets sick And your,

your grandmother buys the pony.

Okay.

Emelie Cajsdotter: She buys the pony

and I am over the moon because now I

think that it's all solved and over.

Right?

Yeah.

'cause I have no idea what you're in for.

When an animal decides to become

your teacher, it's never over.

Right?

So she's being taken from the

riding school and put in the

stable in the countryside where

she can be outside all the time.

It's this open, stable,

she can go in and out.

All the stress is taken away.

So in my world, all that's gonna

happen next is that she's gonna

be well and everyone is will in

Rupert Isaacson: after.

Emelie Cajsdotter: She gets much worse

because at that point, I don't know that

when you have a stress related disease of

some sort, and you come to a place where

you are safe, everything comes crushing

up to the surface at the same time.

Now, this is what I tell people when

I'm out working and this happens to

them now I can be supportive of that.

But this is the first time it

happens to me, so I have no idea.

So I try everything because now

the old desperation is back.

If she dies, my life is over.

There is no opening to the

world of non isolation.

And, and in the meantime, this door that

opened between us in our first meeting

never really closed because it's like this

double swinging door that is like this.

So if I'm with near an animal

that isn't feeling well, all of

a sudden I turn into that animal.

This, I, I can't control

this going in and out.

Rupert Isaacson: This is happening to you?

Yes.

From this point on with other animals?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

Yes.

Yeah.

Particularly animals that are

not feeling well, that, that's

the only pattern I can see.

Mm-hmm.

I'm terrified of it and I

don't really talk about it.

Yeah.

And then I try every treatment under

the sun to heal this pony, like

alternative treatment, vet medicine.

Any other vet that someone

heard of and Well, you know.

You go through it a lot

because you're terrified.

And

Rupert Isaacson: well, it's also

the quest you're called to you, you,

you, you are, you have to in a way.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

Yes, yes.

Yeah, yeah.

And she responds to absolutely nothing.

And to me it's incomprehensible.

Why can't she get better

from anything at all?

Then there is divine interference.

Divine interference comes in a form of

a short notice in the local newspaper.

And it's my mother who spots it.

I mean, we really don't have much

contact and it doesn't work very well.

But she, she spots this notice in the

newspaper that says a veterinarian

from New Zealand is coming to Sweden

to give a series of lectures in the

subject chronic pulmonary diseases

in horses and alternative treatments

of, I mean, that is not happening.

That's too precise.

So my mother says, maybe

you should go to this.

And yeah, I'm going to that lecture.

I don't listen to the lecture at all

because my only focus is I need to

get this man to come and see the pony.

So directly after the lecture, I run

to this old man and, and saying, you,

you have to come and see my pony.

And he says, yes, fine.

We can go tomorrow.

I can borrow a car.

And we go and see your pony

because she's in the outskirts

of, she's now outside of the city.

And I take a bus out every

day and cycle every day.

So two hours traveling every

day to go to this pony.

It's still, the test of

endurance is on, right?

And so we are supposed to meet

the following day in a cafe.

And yeah, I go to the cafe and

he says, well, the car broke

down so we can't go to your pony.

But now you have a choice.

Either you go back to school

and make your teachers happy.

I wasn't too keen on school.

So it wasn't hard for me to skip.

Or you stay here and I will

tell you about what I do.

And I didn't realize that this was

one of these crossroads that really

matters because I was just desperate

wanting the pony to get better.

So I thought, I don't want to

lose connection to this guy.

So I stay.

And this man spent a full day talking

to this kid about what he's doing,

which includes healing Chinese

medicine, homeopathy all sorts of

energetically based treatments basically.

And during this whole day when

we sit in this cafe, I begin to.

Remember something because

somehow none of this is new to me.

This is something that some part

of me already know, and all of

a sudden I understand that I am

meant to do something similar.

This is why I get drawn in and

out of animals because I'm meant

to be able to do something.

So, and it was such a huge

relief to find that foundation

in me already at the age of 14.

Rupert Isaacson: Dot, dot, dot.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

So, then the next day, the car is fixed.

So he says, now we can go to the

pony, because now the car works.

And she responds like

clockwork to the treatment.

Rupert Isaacson: What does he do?

Emelie Cajsdotter: He puts needles he

gives acupuncture and gives her a mixture

of herbs amongst them I know is Chili

pepper because I have to go and buy it.

And she just immediately responds to that.

What was the

Rupert Isaacson: name of this bat?

Emelie Cajsdotter:

Sorry, what was his name?

Tony Frith.

I'm, I'm, I don't know

if he's still alive.

Rupert Isaacson: Tony Frith.

I might look him up later.

Emelie Cajsdotter: He,

he is in New Zealand.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay, cool.

Please go on.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

And and he stays for another

one or two weeks in Sweden.

So I follow him as an assistant.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

'cause

Emelie Cajsdotter: I really want to

learn as much as possible, and he's

very kind in taking this kid on.

And I also realized that being such her

name was period means the tiny one was

such a great teacher that the timing of

healing, she's not sick because of me.

She's not sacrificing herself for

my teaching, but the timing of

her disease and what I have to

learn is absolutely brilliant.

And somehow she knows that because

she doesn't have that fear that I

have, she has completely given herself

to her destiny in a way that is at

that point, still unknown to me.

I mean, I struggle to

keep everything together.

And then he, this, this vet, he leaves

me with a bunch of acupuncture needles,

flies back to the other side of the world

and says, now the rest is up to you.

And, and around the same time,

my mother says the same thing.

My mother, who at that point

suffers from a great depression.

She can't get outta bed.

I remember neighbors having to

come in to sort of lift her around.

She was in a really bad state.

She was in a destructive relationship.

Plenty of those.

But this one may be a bit more particular.

And she tells me this is without anger.

She just says, I, I can't look after you.

Which, which is obvious.

I, I, I will give you a bank account

card and the money, the grant you

get from the government each month

for having a kid, which is about $80,

it's like you will get that amount

of money that I would get for you.

And you just have to, you,

you have to find a way.

Rupert Isaacson: And grandmother,

is it still around at this point?

Emelie Cajsdotter: She's still

around, but she is not really

feeling very well in herself either.

So I get more or less financially

independent at that age.

Rupert Isaacson: This is what,

nineteen eighty two, eighty three?

Emelie Cajsdotter: I'm born 74.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

It's a bit later then it's like Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: It's

like late eighties.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Okay.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And then and I

have one talent that I don't have

to work for, and that is painting.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Emelie Cajsdotter: So I become a

portrait painter and financially

support me and this pony mm-hmm.

By painting portraits from that day on.

Okay.

Which I continued to do until.

I started to do this

as a full-time living.

I mean, I don't have time to paint

now, but hopefully I will go hide

somewhere at some point and continue.

Rupert Isaacson: Bit like me in writing.

Yeah.

Yes.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Okay.

Time.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

So you are now 15, 16.

Emelie Cajsdotter: 14.

Rupert Isaacson: 14.

This happens at 14?

Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

And meanwhile, adolescence has happened.

Puberty's happened.

Yeah.

And has that further opened

up any kind of portals in your

perception, or has that changed any?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

That door I, I'm, I'm calmer

with it because now I understand

that it has a context.

Rupert Isaacson: Hmm.

Emelie Cajsdotter: But what happens

in, in adolescence is that it becomes

messier meaning messies, maybe not,

confusing is maybe a better word

because it's never, I never had, I

had one really frightening experience,

but, and I brought that on myself.

We could do that one too.

It's a short one, but, but all good boys.

Yeah.

All my experiences with, with

ancestors, with other species with.

It always comes from a

source that has kindness.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Emelie Cajsdotter: I, I've, I've

never had an encounter with Ill intent

Rupert Isaacson: except for one you say?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah, except for one.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Tell us that one.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

It was in this time when all of a

sudden I could sit on the tram and

I would be in a different place.

I would see people that would be

deceased or in amongst other people.

It, it, it was, it is like many doors

going like this as adolescents is, even

if you don't add spirituality to it.

Right.

So, and, and I realized that I have to

do something about this and, and, and

this only one bad event I have is when I

have decided to not listen to any of it.

I have this short period,

very short, maybe a few days

when I decide to be normal.

Get an education, get a proper

job get myself a, you know, secure

foundation, not based on all these other

things that no one can see or feel.

And and, and I decide to, you

know, cut your hair and go and

get a job, that sort of thing.

So I, I decide to be normal and

stop this bullshit nonsense.

And and at night when I'm just

about to go to sleep and the room

is dark, I see this headless figure

coming close, closer to the bed.

And it's really scary because

it's just, it's just moving and I

can't, I can't communicate with it

and I can't stop it from moving.

And any sort of prayer or way to try to

get to a a center point doesn't work.

And I turn on the lamp

and it doesn't work.

This, this, this being

is just moving close.

I get sort of heart palpitations

when I speak about it.

Now it's getting to here when I

realize that, wait a minute, this

figure that I'm looking at, this

headless figure is me, it's my body.

I am, I'm, I'm killing myself.

Okay?

Because the feeling was that this, this

individual would come and suffocate me.

Hmm.

It's like, and ever since that

experience, it is like, okay, I

promise I will never do anything

normal and secure in my whole life.

So, and the

Rupert Isaacson: figure, when

you have that realization,

the figure sort of evaporates.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yeah.

Yeah.

They just wasn't there anymore.

Rupert Isaacson: So.

Interesting.

Are you still 14 or are you

a bit older at this point?

Emelie Cajsdotter: I'm

around that like 15.

Rupert Isaacson: Are you having

relationships at this point

or are you very much a loner?

Emelie Cajsdotter: I'm a loner

at this point, and I am slightly

uninterested in romantic relationships

because my friends who has that, they

become slightly boring in my eyes.

Right.

They, they start to sort of

sit inside and hold hands and

they're not out on adventures.

And and

Rupert Isaacson: are people,

are people observing you, other

types of relationship too?

So are people observing, you say

doing acupuncture on your pony, which

back then would've been something

very new and so, and are people

now asking you to do similar things

or are you kind of in isolation?

Emelie Cajsdotter: Mm, I'm in

isolation in the sense that

I'm, I'm just doing this for me.

Mm-hmm.

The things I do for others

is portrait painting.

Okay.

But I've always had friends.

And still do always lots

and lots of friends.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And so you're not

Rupert Isaacson: isolated in that regard.

You are having relationships

just not romantic.

Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: Yes.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And then I moved

school, this is like now I'm probably 16.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Emelie Cajsdotter: And now,

now the pony is back on track.