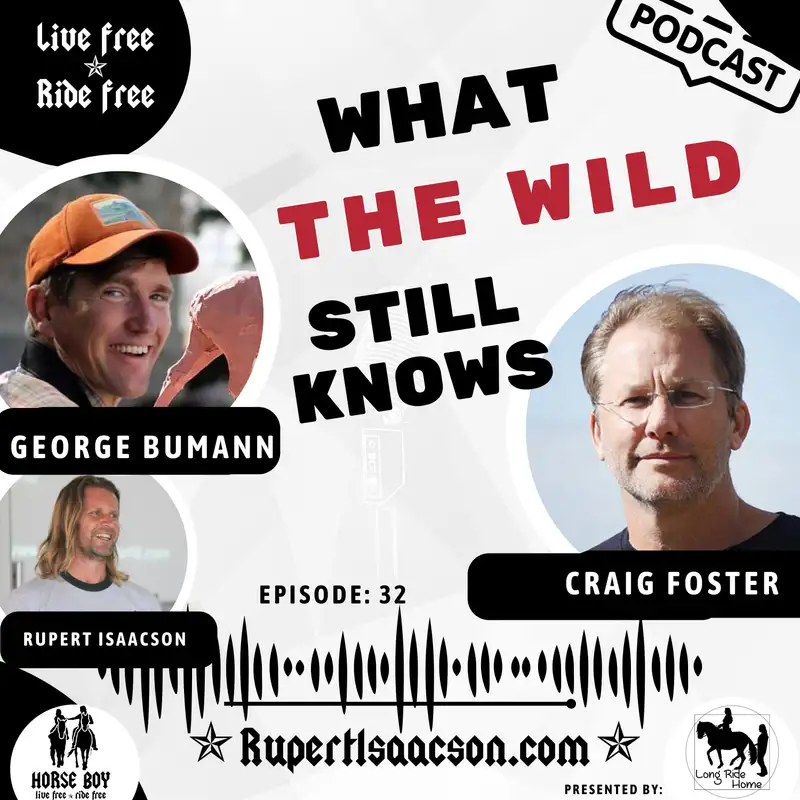

Biodiversity, Belonging & the Broken Heart: Healing Through Nature with Craig Foster & George Bumann | Ep 32 Live Free Ride Free

Rupert Isaacson: Thanks for joining us.

Welcome to Live Free, Ride Free.

I'm your host, Rupert Isaacson, New

York Times bestselling author of

The Horseboy and The Long Ride Home.

Before I jump in with today's guest, I

want to say a huge thank you to you, our

audience, for helping to make this happen.

I have a request.

If you like what we do here,

please give it a thumbs up,

like, subscribe, tell a friend.

It really, really helps

us to make the pro.

To find out about our certification

courses, online video libraries,

books, and other courses,

please go to rupertisaacson.com.

So now let's jump in.

Welcome back.

I've got such a treat for you all.

I've got the incredible Craig and

the incredible George who've ded to

be back on, which amazes me because

why should they, when they've got

so many other amazing things to do.

So, lucky us all right now,

Craig has just come back from

somewhere close to God physically.

Let him tell us about that.

And he's been teasing, I think me and

George with little snippets of where

he's been the last couple of months.

And we've been like, all right,

Craig, just fucking tell us more.

So he's gonna tell us more.

We're gonna hold a gun to his head.

George, if he doesn't make

animal sounds we'll cry.

So, and, and throw our toys

out of the, out of the cop.

But where we left the last conversation

off with Craig, if you, you listeners

remember was we, we were getting towards

the importance of journaling and also

the importance of trying to do things in

tribe and community when we're in nature,

because that's what our species is.

There's, I mean, solitude has its place,

but it's not really fully who we are.

And we also touched on the impact

on the, of the, of the mind

and the brain and the body of.

What does being in areas

of high biodiversity mean?

And you know, both Craig and Georgia,

lucky enough to live in such areas.

The Cape Peninsula of Africa,

Yellowstone National Park, and

I'm here in the forest of Germany.

So I want to kick off with Craig.

Where have you been?

Craig Foster: Yeah, thanks so much

Rupert and great to be here with you.

Joy.

I know you're

Rupert Isaacson: not

gonna tell us are you,

Craig Foster: mum?

Rupert Isaacson: All right.

Where's the place that you've been

that you're not gonna tell us?

So

Craig Foster: yeah, very fortunate to.

I visited this research island

which is 3000 miles off East Africa

in the middle of the Indian Ocean.

Very remote area of a whole

lot of islands and atolls.

And it is what we call the

near pristine environment.

So not much fishing has, has,

you know, pressure there at all.

And it's absolutely startling because

literally everywhere you look there's

a shark and there's a ray, there's

a, you know, manter afin coming up.

They're, you know, just

birds soaring everywhere.

There's predations going on.

Huge fish in the shallows.

You know, you can see tuna snorkeling.

It is large numbers of predators.

And it's just as I was saying, you know,

earlier the, I, I live in an area, in a

beautiful area here, the kelp forest, and

there's a lot of life, a lot of animals.

But this is at another level.

And the, the sheer force of the

biodiversity, the life force that's

pumping through this place, it

does something to your, your being,

to your mind, your body, your

spirit that is hard to quantify.

I mean, it's hot, way

hotter than I'm used to.

There are a lot of biting insects.

You know, it, it's, it's, you'd think

it would be, it would deplete your

energy, but it actually just gives

you this incredible vital force.

And it's, it's fascinating.

I could do, you know, two or three times

more physically than I can normally do.

So it affects you in a deep way.

And it affects your whole being.

It's very, very hard to, to quantify.

And the only, what I can say, what,

what struck me almost as amusing

was, you know, we do all these

things to stay mentally healthy.

Like in a, I do this breathing

protocol and I do in a, the cold work

I do, you know, meditation, all this

kind of stuff to try and keep sane.

Me too, too,

in a place I couldn't resist in a, in

a place like this, I can, I just stop

all of that and I feel just way better.

And, and what it, what

it strikes me is that.

You know, all these things we try and

do to keep sane is just purely, all

we are trying to do is get back to

the state that our ancestors lived in.

Yeah.

Our, our, our design.

That's all we are trying to do.

We are just trying to feel human in

a, in a, in a, in the strange world

that we've created for ourselves.

Rupert Isaacson: George, you live in

one of the flagship biodiverse places.

Oh, look Craig got baboons walking on

his head, in his own, in his own office.

Yellowstone National Park.

Some people think of that.

Tourism traffic jams.

Some people think of that

pre-Columbian, you know, pre

Columbus American wilderness.

Of course it's both.

And of course it's very important

that the crowds can go there because

without access, similar to where

you live, Craig, you know, false bay

in in South Africa, people can go.

People, you know, surfers will

go camp, get in there, people

can go beach, C whatever.

And this, this thing of access and the

desire for access, remains deep in us,

even when we're urban and suburban,

as you say, Craig, there's this, all,

all these things that we do from mind,

body, and soul are simply just trying to

get back to what it feels like to live

in the state.

We're sort of supposed to, as our

species in the habitat we're supposed

to be in, that we now basically no

longer do live in and have lost an, an

almost lost the ancestral memory of, but

luckily it does still drive us there.

So George, before the we hit

record, you were talking about

revisiting paths that are known.

And I like that.

I like the fact, like I revisit

Yellowstone sometimes and I like the

fact that there are certain drives

and a obvious one is the Lamar Valley.

'cause one wants to go there and

see wolves or big herds of bison.

So, and every time you say the Lamar

Valley, there's almost a little party

goes, oh cliche, the Lamar Valleys.

Of course I'm gonna go to the Lamar Valley

for the people that know Yellowstone.

Of course, as soon as you go there and

it's just one road, it's the same road.

You always drive it.

It's never the same.

It's never the same.

The, the animal life that's going on,

the wolves, the bears, the the bison.

You made this point about taking

just hikes that are known hikes and

then just revisiting in different

ways, which I think is another way

of hunting out this biodiversity

that we need for our wellbeing.

Talk to us about that, but before

you do it, make a, could you please

make an animal sound that you might

encounter along that just, it's cool.

George Bumann: Actually,

I'll give you one.

I heard this morning, I was just walking

the dog and along the Yellowstone

River, and as you do, as we do,

there's a, there's a wolf out there.

I never did see it and we didn't have

time to drive across the bridge and a

couple miles back, but there was a wolf

over there to the south about a mile away.

And the way we knew was the coyotes, one

particular coyote was alarming for 20, 30,

40 minutes constantly while we were there.

And who knows how long before and

their typical call was when they're

saying, hi, this is our turf.

Is

that, that sort of lets the neighborhood

know that they're still at home and

stay on their side of the fence.

But it was, this call this

morning sounded like this

and it just went on and on and on.

And they don't do that

unless there's trouble.

That's, that's an alarm bark.

And over the years I've come to know,

even from a distance of three miles or

however far one could hear exactly what's

going on across the valley just by tuning

into the, the natural conversations.

And you're right, the, the goal

really is, is trying to shift our

perspective, even in commonly held

places to see what, what Craig is

talking about in, in common places.

You know, if you're, if you're super

motivated, you know, this might be the

summer of butterflies for you or, or

pick a, pick a topic, pick a location

and, and study it as much as you

possibly can and find those things.

But for us lately, we live here, you

know, and yes, Yellowstone is crowds.

It's, it's been mounting earlier

in the year as the years go

on, and they're staying later.

And, but that's one tiny

piece of a place that's 2.2

million acres in an ecosystem

that's approximately 18 million.

There's a lot of space that has no people

and, and a lot of people enjoy that

ability to get away from what is normal,

normal existence for us these days, and

find that little slice of themselves that

still yearns for this diversity, this

wildness, this freedom, true freedom.

Not freedom of press or not freedom

of, you know, religion, freedom

of being that these places offer.

And for us being here and it's like, oh

my gosh, we all, even living here, we

we're tied to the computer so much and

other things, but making a date on the

calendar and, and sharing it with my wife.

We're like, we're going Thursday.

I don't know where we're going.

We've always looked at this one place

and we haven't walked in there ever.

Let's just go, it might be a half

hour walk, it might be three hours.

And lo and behold, we, we

might stay six or eight.

We, but so often in spending time

with people who may have never

come here before, there is a very

profound sense that some articulate

as a feeling of coming home.

They've never been there before,

yet it feels like coming home.

And I think that space is available

to us, not just in places like

Yellowstone or, you know, the, these

far reaches of the world that, that

folks sometimes get to the best place

to step over that threshold is literally

out the threshold of your own door.

Rupert Isaacson: Well, Craig

made a really good point about

that when we were last talking.

Do you remember, Craig, you were,

you were saying that when you found

yourself in London the last time you.

We're needing to try to

ground yourself with nature.

And of course London actually

does have big parks and there is

quite a lot of wildlife in London.

I was just there last week and watching

the foxes playing on my mother's studio

roof again in the middle of London.

However, you know, when you're tramping

the concrete, like really, really in the

middle of London it's very good to remind

yourself that you're still on that, on the

same planet that yellowstone's on or that

that island in the Indian ocean is on.

Or it used to blow my mind when I would go

up to Scotland, for example, and you could

walk up in Scotland for like five days

and see like two people in certain areas

and say, shit, I'm on the same island

that London is on, you know, which is this

kind of oversized metropolis, you know,

on this small island, but yet it hasn't

actually conquered the island at all.

I do hear you with that

coming home feeling George.

And it can come when we get into the

deep wild places or it can come when we

find the deep wild in the non wild places

because of course it's still there.

And Craig's point about finding the

feeding sites of slugs and on algae,

on paving stones and being able

to see the little toothed edges.

Of how they've been feeding and then

looking at, okay, well what's the

story for the, who's coming now to

eat the slugs and who's coming now

to eat the bird that eats the slugs?

And there comes this, you know,

PID warbler or whatever it is

that we are now noticing, which

we might not have noticed before.

And now we notice, okay, well

there are foxes here and they

are predating on that burden.

Suddenly we're back in tracking mind and

we're doing it in the middle of the city.

That homecoming feeling.

Something that I wanted to ask you

guys, I think all of us often feel, and

I'm sure listeners do too, that when

you enter any real focused interaction

with nature, you basically go into

an altered state of consciousness.

Or do we, or is it only that we

are living in an altered state of

consciousness in the, what modern world

that we live in, so that when we go

back and we find the original state

of consciousness, we consider that

an altered state of consciousness.

Which is it?

Or is it both?

What do you guys think?

Craig Foster: It's such an

interesting question Rupert.

'cause it feels when, when we've

got so much distraction now, and

I, I can immediately go back to.

You know, month or so ago on the

island and no cell phone signal.

I was, you know, often alone for hours

and hours and tremendous quietness

and everything quietens down and you

feel like you in an altered state.

But that then you soon realized

that's the, that was the

normal state of our ancestors.

And while you were talking, I

was thinking, well, you know, our

minds, our minds are built, they're

built from the, the, the bricks

of the minds of our ancestors.

That's how we, we are only

thinking like we are because of

those who have come before us.

Mm-hmm.

So when, when I'm making a fire or

whatever, you know, that deep home

erectus ancestors right there doing it.

So, I think that we are in some sort

of altered state now that has been, but

it's kind of like it's a shallow state

because we've got so many distractions.

So we can't get into that deeper

state that you need for tracking,

that you need for understanding

animals because of all this

technology and all these distractions.

So it's a really interesting

question you ask.

I mean, it can be flipped either way.

What do you think, George?

Hmm.

George Bumann: I agree.

It's a wonderful question.

Because it's, I think it, it gets to where

we've come in the last few centuries,

which is a, a state of being that is,

that occupies a space independent of, of

that which our, our brains building blocks

were founded on, as Craig said, and, and

we're just sort of in this maelstrom of,

of activity and input trying to adapt

to this new situation that is so foreign

to the very substance of what we are.

And so, yeah, when we do get into those

spaces and states, it's, it seems altered

and yet those, those states are where

the greatest listening, the greatest

discoveries, the greatest creative.

We always say this.

My wife and I, Jenny will go

for a walk and we do it out

of exasperation sometimes.

Like just, we need to get away.

We need to get out.

We're gonna drive, not we

could walk at our back door.

We just to mentally create this

space, we drive somewhere and

instantly we're interacting

Rupert Isaacson: better, more genuinely.

Question.

That was gonna be my next question.

What do you guys think

about nature and conflict?

Resolution, high biodiversity.

And conflict resolution

just in your own lives.

Just go on with that, George.

Let's go back to your wife.

And she rises the pan

head from the corner.

If I

George Bumann: could make an

analogy, it's like the pores open

up, you know, it's this flow through

that those settings instill in

us like it, we're more creative.

We, we might be talking about

an idea for a program or an art,

you know, a piece of writing.

And these ideas just,

they start exploding.

Like, oh, we could include this

and do this, and yet sitting in

the house or sitting at the office.

It's just these, these, this

mental space that we sort of

build is, is not serving us.

What serves us is to, to be more

permeable, I guess, is the way that

it feels like to me when we're out.

It's not me, it's not you.

It's not even us as, as a

reference to the people.

It's, oh my gosh, did you just see that

bird rocket through after that other bird?

Oh my gosh.

The, the, there's a rabbit just jumped.

Did you catch that?

And you know, it's a great example.

A friend was doing a lot of

urban school children groups,

and they give them all a camera.

And the first three days,

all of the photos were of

themselves and their friends.

At about day three, there's a flower.

There's a mountain scene

Rupert Isaacson: that's interesting.

There's

George Bumann: a geyser, there's

a, a textured log on the ground.

And to me that speaks to this

inherent curiosity and, and, and

desire on our part to, to sift into

something bigger and more than us.

And as a result, we find, I feel

like I personally find more of myself

or step out of myself as often as

needed by entering those spaces.

Craig Foster: Can I add to that?

Yeah, please.

While I've, I've got the idea in my head.

So you're asking about the conflict

resolution in these spaces and

mm-hmm.

Craig Foster: For me, it's so

unnatural that we put so much

pressure on our human relationships.

It's just like that's

never happened before.

Mm-hmm.

So, you know, in, in the world of our

design, we have these relationships.

With all the tiny creatures.

We've got relationships with predators.

We've got the relationships

with prey, hundreds and hundreds

of these relationships with

different forms of animals.

And a lot of our being

is taken up with that.

Now we sever that.

All those incredible threads, those

bonds are severed and all the pressure

is on these human relationships.

That's so true.

When you go into these spaces, it's

those threads start to, to reweave and

it, it just lifts all that pressure

on your wife or your children or

whoever, and suddenly you are working

with this pantheon of creatures

and humans are just part of that.

And that feels far, far more peaceful.

Rupert Isaacson: You know what, obviously

Craig and I, you share this we share

this experience in the Kalahari with

son Bushman who are non warriors and

appear to be the human blueprint.

So it would appear that humans are

not really warriors that this comes

in somewhere after agriculture and

it, so what is gets so confusing,

I think, is that if you're involved

in agriculture or herding, you are

involved in nature very deeply and

you still have these big relationships

with all these different species.

You still have.

The weather matters.

You know, you okay.

All of the things we know and yet out

of those cultures came, war and conflict

creation rather than conflict resolution,

overpopulation for some of the apocalypse,

all of that stuff, fam pestilence all

from overpopulation, you know, whether

it's in villages, whether it's in cities.

But that's 10,000 plus years ago now.

So for most of us, us, you know,

including the three of us sitting

here, we're inheritors in our immediate

DNA of that conflict warrior culture.

And, you know, you and I, Craig,

our forebears were colonial pirates.

You and I were lucky enough to get

involved in land rights restoration

of the indigenous, very indigenous

people that our ancestors had

a part in kicking off the land.

And it was good and felt good to pay

that karmic debt to a large degree.

You know, George, you are, you are

sitting there in Yellowstone, 19th

century earliest National Park formed.

Why?

'cause they kicked the people out

and you know, the Nez pe Indians,

I dunno if they were the only ones

there, but they're certainly the ones

that the stories are told because of

Chief Joseph running away from the.

The American Calvary hunting him

to, you know, pacify the West.

And now we come out of that conflict

society, that Viking society, Booman,

you know, your Germanic you know, Craig,

you are Anglo-Saxon, Dutch, Germanic.

I am too.

With that little bit of Ashkenazi

Jew that just won't go away.

And the Rabbi Rupert.

But nonetheless we haven't, us both the

ones who helped to Sav, as you said, and

the ones who wanted to remain connected.

And

so

we've been lucky to find ourselves

in these places of di biodiversity.

The human mind is biodiverse, right?

The human mind is like

a, it's like a forest.

No axons like trees, dendrites going

out to wire like branches, like twigs

branches and roots to wire with others.

And it seems that if we get rigid

in our thoughts, we become like a

plantation of eucalyptus or pines

that someone's gonna chop down or.

If their mind is allowed to do what it

needs to do, it becomes like a wilder

ecosystem with more possibility when given

that most people are going to be coming

out of this feeling of constant conflict.

This feeling of constantly being in the

amygdala in with cortisol, the stress

hormone, that we have this crazy tolerance

for it, it seems, but it drives us insane.

You are both in the business of bringing

the stories from the wild places to

people screens, to bringing people

directly out into it, to creating

art that tells the story of that.

How do you see your roles there

as conflict resolvers, whether on

the meta scale or the minor scale?

I'd like you guys to talk about what

you do from that perspective and

how can through that, how can people

listening pick up some tips about how to

resolve internal and external conflict

through direct, interactive with nature

and bringing the stories of nature

that they've tracked back with them.

Do you wanna kick off with that, George?

And then do you wanna.

Just Sure, sure.

I can

George Bumann: take a stab at it.

I, I think it's a, it's a very potent

question and and one that, that

needs to be worked on all the time.

I would say because we, by our very nature

have, have done a lot of things that,

you know, if mankind had its

chance to do over again, maybe

we would pick a different path.

But here we are, you know, and I

think one of the greatest services

to, to life and to community is,

is to tell this story and, and in a

way that includes all of the voices.

You know, I spent a lot of time

listening to wild animal conversations,

and in nature you quickly realize that

there is no Outlander, there is no

immigrant, it is only us in this moment.

You know, so poo-pooing the starling

because it's in your, it's European

ancestry poo-pooing the, the dandelion

because most of those species and or

variations were brought to North America,

you know, trying to eradicate these

things when in fact, you know, there is

a, certainly is a place for maintaining

native plant communities and so on.

But in nature, all of the conversations

and all of the speakers are valid.

Accepted and contribute.

Mm mm So true.

And so when we tell the story of

Yellowstone, you know, there on

record there's 30 ish, 35, you

know, tribes that had affiliations

here, it's probably closer to 50.

We do our very best in our programming

to bring those voices in, let them

speak for themselves, not tell their

stories for them, and, you know,

curate, curate the best we can.

A a, a re and a res sorting of

the deck so that we have a picture

that fits the current time.

It's, it's so easy and we do it

subconsciously, is to, to tell

the story from our perspective for

which that's all we have, right?

My Germanic ancestors were the first

settlers in the part of New York that

was cleared of the Haudenosaunee people

when George Washington cleared the entire

landscape of those tribal allies to make

way for, for our, my European ancestors.

And so I can't undo that.

But what I can do is make sure that

what's going on now is honest about that

and honest about what we've done to

the, the tribes of non-humans and, and

allow other people to the tribes of

Rupert Isaacson: non-humans.

That's a book title.

George Bumann: Hmm, perhaps so.

But, you know, it just diversity.

We crave that diversity.

You know, you, you, you want to get

all the baseball cards you want, all

the, the knick-knacks, you want all,

we, we crave that, that sense of,

of variety as, as the spice of life.

And we are not the keepers of

that as an individual being.

We must be in community.

We must be in association with others

to supply what we have our blind spots

for or have neglected or have missed.

And I dunno.

I'll stop there.

I'll, I'll let Chime

and Craig chime in here.

Craig Foster: So what came to mind

when you asked the question rep was

fundamentally what I am

trying to bring across.

And so the help of a, a wonderful

team is this very simple idea that

Mother Nature is the shareholder of.

Everything we do, all our

businesses, all our endeavors.

She is the, the foundation,

she's the life force.

She's everything.

Yet we've forgotten that.

I've said this before, but I

purposely say it again because

it's such a fundamental thing.

Like if you take away the biodiversity,

what we are talking about now,

every single thing will collapse.

We won't be able to breathe,

eat, function, and, and this

is what we've forgotten.

So

Rupert Isaacson: fire up all that ai.

Are we gonna power it?

Yeah.

Not through nature, it's just,

Craig Foster: it's just a joke.

Everything will collapse.

Yeah.

Ar ar go very fast.

So it's like, if we could just put

all this incredible mental force

we've got into looking after the

most foundational thing that will

affect every single human's life on

this planet more than anything else.

It seems the logical way to go, but people

have somehow conveniently forgotten this.

So it's trying to bring that

story back and how you do that.

I think, you know, ultimately

it's through storytelling.

'cause storytelling is this foundation.

For the way we operate.

So everything that we see

around us is based upon a story.

We are the storytelling

Rupert Isaacson: ape too, you know?

Yeah, exactly.

We have the larynx.

Yeah.

Yes.

Craig Foster: So, so we need to

change the story from this massive

extractive force to one of reciprocity.

And, you know, the, the, one of the

new and interesting ways we are trying

to do that is through this project

we've called 1001 Sea Forest Species.

And I dunno if you want me to go

into some of the detail now, or we

want you to go into not the detail

Rupert Isaacson: now.

Craig Foster: Okay.

So it's, it's taken many years to get to

the point we are, and it'll take quite a

lot or more years, but essentially what

we're doing is studying 1,001 animals

in the great African Sea forest and on

the, the intertidal shore, getting a

beautiful scientific page on each animal.

Its proper scientific name.

And then layering into that powerful

stories, like these incredible stories

that George tells us of these face-to-face

encounters with these incredible animals.

The, the, the personal stories

that pieces of their secret lives.

Then adding to that, these, you know,

high level photographs that are almost

like love letters to these animals,

beautiful images, short films on them,

anecdotes, incredible bits of behavior.

So suddenly you've got this

interwoven digital platform

that stores all the memory.

'cause I'm already forgetting half

of what I've already encountered.

It's too much.

But if I can store it in there, and the

prof we working with and Jannis, the PhD

biologist and all the other team members,

we put it in and we create this hive mind

of this incredible ecosystem hive mind.

It's like a

Rupert Isaacson: hive mind.

That's the follow up to

the tribes of nature.

Yeah.

Craig Foster: It, it, it's this incredible

pulsing beating heart of the, these

creatures and the smallest ones that you

can, you know, most people will never,

ever see, have stories, have a voice, and

then you can show other people in other

parts of the world they don't have to go.

And do it at this intense level.

They could just take 10 or 50 animals

that they're in their backyard

really, and do the same thing.

Build a a hive mind of them

and let them speak as well.

Let biodiversity speak.

Let the, the divine creation that

is manifest in nature have a voice.

It's a very, very powerful way of getting

this idea back that she is this thing

that's kept us alive from the beginning.

And if we, if we aren't careful with her,

we, we, we gonna be extinct, basically.

I mean, it's a horrible thing to say,

but she's holding us up every second.

Rupert Isaacson: Give us a story

on one of the things that is so

small that we don't even see it.

We'll notice it.

That's in your Thousand

One Species Project.

Craig Foster: I was just working on the,

it's called the Cape Marella this morning.

Rupert Isaacson: Cape Marella.

Craig Foster: Cape margin.

And these are tiny little predatory

snails, like a cleanup crew.

They live underneath the sand and they

put their little proses up through

the sand and they've got incredible

smell and they're just waiting.

And if any animal is dead or

dying or injured, they come out

on mass and they just envelop it.

And they, they consume it

Rupert Isaacson: in the kelp forest.

Craig Foster: Yes.

And you know, 99.9%

of people have died.

They've definitely never seen one.

So if an octopus makes a kill, they

just onto that kill immediately.

They clean it up, they clean the smell up.

And what's amazing is they have this

ability, and this is like the secret

life, if they get a piece of flesh or

a tiny animal that's died, they can

wrap it into a bundle and pop it into a

compartment on the back of the mantle,

and then they charge away to try and get

away with this thing that they can eat.

And I've got images and

pictures of this extraordinary.

Are there other trails

Rupert Isaacson: snails trying

to stop them when they do that?

Yes,

Craig Foster: yes.

They, they, they're all fighting like

rugby scrumming to get hold of this thing,

but it's so beautifully wrapped that they

can get away and then they go underneath

the sand and away and then consume it.

So, I mean, it's just there.

These hundreds and hundreds of these

incredible stories that have now.

They've just been sitting on this giant

hard drive, just, you know, what's gonna

happen to, how did you find out about

Rupert Isaacson: the Cape Marella?

Craig Foster: I've been, you know,

looking very, very closely at Octopus

and their kilts and then wondering what's

happening afterwards and looking very

just, you know, staying still okay after

a kill, just holding on underwater.

And then you see these tiny little

proses coming up, these tiny

creatures coming out, and some even

like coming down from the kelp.

And, and then they go inside the shell

where the, the predation being made.

And if you're not quick

enough, you don't see them.

And then suddenly the shell is clean.

They've just cleaned out everything.

So it's just from this fine observation

that you, you've see them and then it got

these incredible, you know, images and

video of this, of these amazing behaviors.

And you, you get this cent, this,

this smell, this just phenomenal.

Rupert Isaacson: Before we hit the

record button, you said that it

was gonna take about a decade to

get all this material together.

What's your a, do we have to wait that

long, or are, are you gonna release it

in sort of watchess that we can enjoy?

Yes.

Yeah.

So fairly soon

Craig Foster: the first layer

of the app will be available.

You don't need wifi, and people can

take it out into the field and literally

anything they see will be in there.

And it's a bit of a tracking

thing to find, find it,

Rupert Isaacson: anything they see in the

kelp forest or anything they see in any.

Craig Foster: Anything they

see on the shore or in the

kelp forest will be in there.

Okay.

Okay.

It's very unlikely they'll find

anything that's not and then that

you'll be able to get a sense for it.

But we are gonna add the layers and

layers and layers as as time goes past.

Rupert Isaacson: Craig, you know,

you've been one of my heroes since

I've known you, but you just confirmed

why you are one of my heroes.

It's like

one of the things which we do

in what we call movement method,

which is the way we work.

It started with autism, but now it's

schools or people with, you know,

looking to for a neuroplasticity boost.

Is this thing of, okay, fine, not

everybody can get into the forest of

Germany immediately or down into the cult

forest or into Yellowstone or wherever.

And yes, you can learn to see the

slug tracks where they've eaten in

the middle of London, but when you're

a kid who is born to be sort of awed

as much by the big stuff as by the

little stuff, you may or may not be

open to something so detailed at least.

You might need to go through

something a bit more obvious before I.

You can look for the fine detail.

And one of the things which we do

therefore, is because people are stuck

in classrooms because they're stuck in

therapy offices, which are just shit,

you know, they're just linoleum and

fluorescent strip lights, and so I'm

gonna hear it make you feel better.

It's like, no, you're not.

It's, there's no way you can possibly make

me feel better because look, you know.

No, but as you say, severed from the

ancestral connection with nature,

how would that therapist even know?

So we have this thing about just

bringing the outside inside.

So generally we do these classroom

makeovers where I'll say, I

just want to see antler in here.

I want to see bone, I want to see

sheepskin, I wanna see animal heights.

I wanna see sand.

I wanna see wood chips.

I wanna see different types of light.

I want to see stuff that would be

in a hunting and gathering camp

so that when the kids touch it, it

will trigger an ancestral memory.

And there's enough studies done now

just showing how, for example, toys

made out of natural objects, you

know, affect the brain better than

toys made outta plastic or whatever.

You guys do this on a meta scale, you

know, you bring back these stories, Craig,

that the films that you've made have

made peop millions, tens of millions of

people now look more closely at nature.

You've, you've really.

I've done an amazing job with this.

You know, George, your, your books

and the art that you do, I feel

composites of stories that bring

them into human environments,

that amazing place that you live.

And, you know, I said, talk to me, George,

about the process of putting natural

story into art and then giving the,

that natural story to people to bring

into their non-natural environments.

And what's that process for you?

Hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: From an

emotional point of view as well.

Yeah, I, I've seen you and, and

anyone listening should go and find

the YouTube video of George will put

a link to it doing a, a, a, a Clay

Wolf and a TEDx talk as, as he's

talking you should see him do it.

This is story.

George Bumann: Yeah.

Yeah.

I think it's important

that we get away from

Craig's waving a, another one of my

creations in front of the camera.

Okay.

It's a Clovis reproduction a spearpoint,

one of the older technologies from the,

the, the, the prehistory of North America.

And ironically, one of the most

difficult points to reproduce is that

why is it so difficult out of interest?

Largely in Wow.

Because it can you see the fla that goes,

I would've thought that from the bottom.

A real

Rupert Isaacson: artifact.

George Bumann: Yeah.

That's why I sign them.

So if they somehow fall outta someone's

pocket, they don't get confused for it.

I've had some friends pull it over,

pull one over on their, their friends

with some of my reproductions.

But the, the, that, that about

a 12,000 year old type of point.

Correct.

Yeah.

Correct.

Yeah.

And this is the type of weapon

reused to hunt mammoths and wild

horses and camels and things

that existed in in North America.

At that time what makes it tough

is that flake that goes up the base

from the bottom toward that the tip.

And to get that to happen on both

sides, you break I've broken hundreds

to get to just a handful that I have

completed, and I only give them the

people I really appreciate in person.

So maybe I was gonna

Rupert Isaacson: say thanks

for the Clovis point.

Yeah.

George Bumann: Well you need to,

we need to meet up in, in person

and, and perhaps one will appear.

Craig and I had that on his book

tour as our mutual friend John

was kind enough to, to hook us up.

But back to the, the

topic of, of just art.

I think we need to step away from

the story as it, we've been referring

to it as a, a spoken word story.

Craig's doing it beautifully in

the digital realm with his films.

I'm doing it with my hands.

I'm, I'm making sculptures.

I'm actually.

I think I can show you one of these here.

This to me is a story.

This is a miniature basket I made from

a local plant for my wife for Christmas

and died some of it with black walnut.

But in this little basket is a story of

Rupert Isaacson: something

brilliant, George.

George Bumann: It it's, well, thank you.

But it, it has its own story.

There's a, I have the relationship

I have with this patch of plants and

I curate them and take care of these

plants and weed out the, the dead stems.

And I've learned so much about

my home through these plants.

And so it comes with this, this

experience of, of place that when you

look at a, sadly when they're in museums

and separated from the people and the

landscapes where they're created, these,

these historic works, you just feel,

maybe not the details of, but the thrust

of this, this relationship with the

landscape, with nature, with one another.

And when I'm working on a

sculpture, I don't use photographs.

I, I sketch either on paper or I

sketch in clay or wax, and I may

finish the piece in the field.

Although a lot of pieces, I have to wait

till that bison is back in that same

coat pattern next year to finish it.

But a lot of times those sculptures

might be 5, 6, 8, 10, 12 years in the

making because I don't want to create

just a representation that visually thi

makes you think of a wolf or a bear.

But these are, in essence my

travel logs from years and

years of really detailed study.

So I have my own data sheets.

I had a phishing tackle box and I threw

all the phishing tackle out and made

my own data sheets to take 50 plus

measurements on every mammal that I

find deceased and have tape measures and

calipers and dissecting knives and rubber

gloves and pencils and pens and, and all

of this making death masks, which was

a, a, a historic thing that artists did

of, of people when someone passed away.

It was a common thing in the, the 19th

century to make a, a plaster cast, a

death mask of their face, you know,

making those of animals that, that I'm

able to, deepens an understanding and

appreciation for them that I see in

the movement of the sun on a given day.

I spend the entire day watching elk

just to understand what their body

looks like and how it functions at

exactly this time of the year with their

coat pattern exactly the way it is.

And you don't see that subtle relief

of the ribs and that subtle push of

the ileal crest of the pelvis until

the sun gets just at a certain angle

and they turn at a certain angle.

And so what I create in clay, to

me, is the accumulation of just

mountains of time paying attention.

And the sculptures to me are

also an excuse to look deeper.

You know, Craig's collections and, and

his video and, and his journals function

similar to mine in that way, where they

help inspire more questions or, right.

Well, what you know, what if

this was an adult instead of

a sub-adult or a juvenile?

Oh my gosh.

Holy cow.

And then there's other elements

within there, like she's, she's

walking a little in funny, oh my gosh.

She, you can actually see the very subtle

bump on her metatarsal bone where she

must have broken her leg at one point.

So the stories in these layers,

like what Craig's would do, it's the

story helps build the next story.

The he, the story helps you look

further into the experience.

Rupert Isaacson: I so agree.

You know, when we signed off from

our last conversation Craig, you were

talking about journaling, so of course

I probably have to start journaling.

So I found myself very quickly after that.

It was journaling, but story,

it's just gathering story and

exactly as you just described,

George, you know, this observation.

So a friend of mine who runs a fox hunt in

Northern Germany, but it's not an actual

fox hunt because I don't do that anymore.

We lay a scent and we ride after

that, but it's still, the hounds

have to work it out and so on.

Asked me to come up and spend three

days hunting, three, three days in a row

hunting because they needed the support.

They were short of manpower

and I said, of course.

And not my horse though.

And normally when you go and you trust

your life to the unpredictable country,

you particularly if it's gonna involve

jumping, it's better to be on a horse

that you have a deep relationship with.

Because, and there's a story

there, but it wasn't, I, yeah.

And I was in an era of

Germany I didn't know.

And we're in this for us.

And you are, I've got Craig's

words going in my mind as we're.

Laying the lines and helping the

hounds find the lines and saying, yeah.

In this, in this highly human affected

landscape that we're in, it's still,

we are, we are now the Wolf Pack.

We're taking the place of

what the Wolf Pack was.

It's just a modified

human wood pack wolf pack.

And now that particular form of it that

we are doing is about 300 years old.

But, and we're, I'm, I'm on this

horse that's designed to run really

fast and jump these fences, which

was evolved at exactly the same

time 300 years ago for this purpose.

Which was taking stock from the original

step herders of Central Asia, what we

call the turman horse, which is now

the ancestor of the thoroughbred horse

and mixing it with the Arabian horse.

I'm on an Anglo Arab, as they

call it, very hot horse to ride.

And this has now come up to Northern

Germany, but actually they would've come

in here long before because the Goths

and the Lombards and the ards and the

vandals and Thewas and the alimony and

all these tribes that would've been pushed

into this part of Germany from the east

by the Huns because of climate change,

you know, 2000 years ago, established

these cultures of the horse here.

And that we are still actually kind of

the indigenous people that were always

here practicing the same culture.

And as I'm thinking this,

we, the hounds bring us past

these, this, these megaliths.

And these old burial mounds, these

old stone burial mounds, dolmans, you

know, with the, with the capstone on

top from five, six, 7,000 years ago, I

didn't even know were in this forest.

And I had had an experience

like that before.

In Cornwall, once hunting in the mist.

In the mist came up.

And I found out I was in the middle of a

stone circle on my horse and but alone.

And you feel that touch

of the divine comes.

It's like the, the old Celtic called

ano, you know, with you in that moment.

And you must give respect and ride on.

And so I get the sense of the story

of the horse that I'm on is being

brought in here by these tribes.

And then these were the same tribes

that would've had a common ancestor with

these guys thousands of years before

even that building, these grave mans.

And then, what are we?

But the human wolf pack.

Okay, but now that the, the

hounds which create the wolf

pack, where are the wolves?

And that is, ah, but the wolves are

coming back in all these parts of

Germany for the first time in 150

years, the wolves are coming back.

And not, in fact, we had been warned going

out that we could run into wolf and were

we gonna, would our hos be all right?

Were they gonna be all right?

Blah, blah, blah, blah bum in this

area that 150 years, years ago wiped

them out despite the fact that there

was this deep, connection with nature.

This is the area where all the

grims fairytales come from.

So little red riding with forest

is one hour north of air Wolves.

Don't get a very good

rap in that one, do they?

SEL and Gretel for it's an hour.

The other way, the sleeping

beauty castle is just a couple of

hours from me, blah, blah, blah.

And here we are in amongst all this,

in, in all this story, living this

story, still practicing the story

and the older story is coming back.

First these mega lists.

And then the wolf itself, not five

days ago in the same village that

I'm sitting in here, which is much,

much closer to the city where, pretty

close to downtown Frankfurt here.

Someone, my, my friend Philip, sends me

a picture of a big male wolf just walking

on the hills, just on the other side from

this window that I'm pointing at here.

And this thing of full circle and con that

is that not conflict resolution, right?

And to bring a story into oneself and

to sort of live it and ride it if you

like, and experience it as a living story

and realize this is what's going on.

And then think, oh my gosh, even that

comes from conflict and realize, because

why are all these wol here anyway?

'cause of Chernobyl, because of the,

the nuclear disaster in Chernobyl

in 1986 where they had to mark

off a huge area of central Europe

and say, no one can go in there.

So what happened?

Nature just reestablished itself.

And apparently there are these wolves

that are showing up here, have a gene

that's been switched on, which is anti

radiation, which is why they thrived.

And now they, they, they've overpopulated

that Chano area and they've gone out and

that's why they've now come to Germany.

And that's why they're now showing up

in the Netherlands and Belgium where

they, you know, have been gone forever.

Wiped out in the little red riding

hood time, so on and so on and so on.

And conflict and conflict resolution.

As you know, if you followed any of

my work, I'm an autism dad and we have

a whole career before this podcast in

helping people with neurodivergence,

either who are professionals in the field.

Are you a therapist?

Are you a caregiver?

Are you a parent?

Or are you somebody with neurodivergence?

When my son, Rowan, was

diagnosed with autism in 2004,

I really didn't know what to do.

So I reached out for mentorship, and

I found it through an amazing adult

autistic woman who's very famous, Dr.

Temple Grandin.

And she told me what to do.

And it's been working so

amazingly for the last 20 years.

That not only is my son basically

independent, but we've helped

countless, countless thousands

of others reach the same goal.

Working in schools, working at

home, working in therapy settings.

If you would like to learn this

cutting edge, neuroscience backed

approach, it's called Movement Method.

You can learn it online, you

can learn it very, very simply.

It's almost laughably simple.

The important thing is to begin.

Let yourself be mentored as I was by Dr.

Grandin and see what results can follow.

Go to this website, newtrailslearning.

com Sign up as a gold member.

Take the online movement method course.

It's in 40 countries.

Let us know how it goes for you.

We really want to know.

We really want to help people like

me, people like you, out there

live their best life, to live

free, ride free, see what happens.

Do you feel guys, that what we're

having to learn how to do again in our

conflict culture is to learn how to

track, learn how to hunt nature itself?

Again,

George Bumann: that one's you, Craig,

that's a tough one.

I just wanna point out

Rupert Isaacson: to a long time, so

we had any animal sounds, George.

Yeah.

I am missing their sounds.

I, yeah.

George Bumann: And what is

that common Raven telling us

what my turf, this is my home.

Explain yourself because

you weren't invited.

Explain yourself,

Rupert Isaacson: Craig.

Are we having to, are we, are

we indeed having to learn how to

track nature again as a species?

Craig Foster: I think we have

we've definitely lost track.

I mean, to be this idea of being in

conflict with the great mother mm-hmm.

Which we are in now, is a, is

an absurd, absurd place to be.

I mean, why would you you know, wage

conflict against the very thing that's

nurtured you from the beginning of

your species and keeps nurturing you

despite everything is thrown into it.

It, it is, it unfortunately

is a definition of insanity.

But it's understandable given all the

pressures, you know, that the, this

shifting baselines and each new generation

gets forced into these strange places and

these linoleum covered environments where

there's no hint of ancestral connection.

You know, the knowledge of the elders

you know, no longer there to guide us.

It, I think it's absolutely critical

that we, we rarely start to.

Understand where we are sitting and

how, just how fragile our position is.

Because this great mother

that's, that's, that's there.

This, this biological intelligence,

this biodiversity is, is very strong.

We can push her down and she will make

you know, life impossible for us to live.

And then she'll bounce back in

a, in 10 million different ways.

Like she's done the before.

Just

like the wolf.

Yeah,

Craig Foster: yeah, exactly.

It's just like the, the

wolf from Chernobyl.

But I think, you know, it's easy to

see ourselves as a dark species, but

we are actually so beautiful in so

many ways, and we understand at such

capacity for this, you know, loving

the mother at such a deep level.

You know what George is talking about

this, the, the, just watching this elk

and understanding them over the years,

that's a form of deep love and respect.

Mm.

And in

Craig Foster: his art and this incredible,

like clover's point when he gave it to me,

I was just, you know, deeply emotional.

'cause you can feel if, you know,

napping and stone tool making

the tremendous energy, power and

practice it takes to do this.

I think it took him 30 years

to master these points.

Am I right, George?

Yeah.

The, the, the amount of the

capacity for the love we have is

just tremendous in all humans.

So we actually, I think, are

a very beautiful species.

Mm.

Craig Foster: And it's worth keeping

us alive, but we just have lost track

completely of you know, our, our

relationship with the bigger forces that

actually are in charge of our future.

George Bumann: And a lot of it's

distraction, I think certainly the

conflict and is in the background

working on us, but the distraction that

we referenced earlier is, is enormous.

Mm.

You know, so often I'll take students

or class out into Yellowstone and you

know, the intention is to understand,

you know, bird language for instance.

And we go out and we just sit.

And the only rules are no

watches, no phones, no nothing.

I'll keep track of the time.

You just sit and watch and listen

and to some people, so they're

like, we don't have to do anything.

So initially that, that and alone for a

lot of people is, is a, is a huge relief.

We're we're human doings.

We're not human being beings.

Well that can also be

Rupert Isaacson: very scary, can't it?

George Bumann: It can.

So you kind of curated

Rupert Isaacson: and your

mind I'm not doing something.

George Bumann: Yeah, exactly.

Exactly.

And, and that's, I struggle

with that very much.

Yeah.

You know, what, what

is this thing about me?

Working on, on something or just, just

reading a book for crying out loud.

I, I should not, is

Rupert Isaacson: that not because,

is that not because we actually ought

to be kind of tracking all the time?

Do you, do you remember which of

the guys was it in the Great dance

Craig, who said of the three son

hunters that you are always tracking?

Craig Foster: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: You are

never not tracking, right?

No,

Craig Foster: not, yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: And is our, is our desire

for distraction, simply our desire to be

tracking when we're cut off from that?

Mm-hmm.

Craig Foster: Yeah.

'cause it's, it naturally

just animates you and to you.

But now you take that away,

the mind is searching.

That's an interesting idea,

Rupert Isaacson: but I

guess you're right, George.

You have to have a certain quietude to

create the space where the white, we

have to give ourselves that greatest

George Bumann: gift.

That greatest gift is the time and space.

And sometimes you have to legislate it

for yourself, you know, put it on the

calendar like a doctor's appointment.

If you look at other species who

are contained and caged, they start

these repetitive behaviors and

self damage, inflicting behaviors.

We, we in many ways

resemble that caged animal.

We are not exerting ourselves in the

way that our nervous system needs.

There's been, I'm, I'm in the process

of, of correcting my own eyesight,

naturally wor glasses since I was 12.

And one thing I didn't write about in

the book with the magpie experience

that we talked about in the last

podcast episode was I had this moment

of that altered state, but I also, and I

didn't write about this, had absolutely

perfect vision for just a few seconds.

And what I've found is through this

process and this, this was a technique

developed and studied and figured

out in New York in the 19 teens,

late 1918 hundreds and early 19

hundreds, it was the end of glasses.

The eyes are an extension of

the brain's nervous tissue.

And when the brain is out of sorts, the

eyesight is out of sorts, quite literally.

You know, when I'm out in nature

and I feel that relaxation with

practice in this technique known as

the Bates method I get a lot more and

longer periods of clear vision now,

and as one keeps doing this, you.

You don't need your glasses anymore.

Whether that's nearsighted,

farsighted, I have astigmatisms.

I can see the top of

that mountain right now.

I can see individual trees

and they've done studies on

native Alaskans at the time.

They started educating those, those

native children in westernized schools and

their eyesight went down precipitously.

And yet in the native community

where the elders were taught in the

old ways and lived in the old ways,

they had perfect vision into their

seventies, eighties, and beyond.

What is the Bates method?

It's on the whole, it's a technique

that teaches you to relax.

It is the think of a water balloon is

what basically what the eyeball is in any

slight influence on that changes the shape

and hence the clarity that you perceive.

And we, we have these clench fists.

Yeah, some people keep them in their back.

Some people keep them in

their legs, their jaw muscles.

And those of us who have need

vision correction often keep them

in these muscles we don't even know.

We have in the orbits of our eyes

that are squeezing the eyeballs

in ways that distort our vision.

And as we learn to let those relax, the

eye takes its natural and healthy state

and we just see clearly, it then affects

our mental space, our mood, our, you know.

I've been going without glasses for a

while, and a lot of that early state,

I felt isolated from my community.

I wouldn't recognize people in the grocery

store and they'd have to wave, you know?

And I think a lot of things that

go through our minds, if they,

even if they don't distort our, our

actual eyesight, they isolate us.

These lessons of nature are to expand us.

And through the expansions, I

personally feel like it's, those are

the spaces where I'm my best self.

I'm healthier, I'm more creative,

more relaxed, you know, and we,

Rupert Isaacson: I was, I was doing a

podcast the other day with a neuro, a

neuroscientist called Cheryl Pratt and

University of Washington, and she made the

point of that when we are forced to have

focused attention for an unnatural period

of time, it's so exhausting for the brain.

It's, her book is the neuroscience of You.

It's really good.

And they look at not how all the

brains are the same, but how each

brain is different in her lab.

But that one of the generalities is that.

Forced attention school,

but also living in a city.

She said, because if you're in a

non-natural environment, you're actually

honing in constantly on these framed

points of attention because there's

nowhere to generally rest your vision

that in nature, because the lines are

soft, you can, you go from sharp, focused

attention and then immediately relax.

She was making the point that A DHD

is largely brought on by the mental

exhaustion of being forced to have

too much focused attention and the

fatigue that the brain goes through,

rather than the tracking skill, which

of course is what it is, of being able

to narrow in zip, but then softly focus

out again and z and focus out again.

It's always balanced and actually

you probably spend most of your

time being able to rest the brain

and as you say, rest the eyes.

Mm-hmm.

Craig Foster: That's, that's so

interesting because this, that's what

I've noticed and, and I know George has

noticed this too, in a, in a big way,

that when you are in these places these

near pristine places or places of, of.

What I call the beating heart.

When the biodiversity's in all in place

mm-hmm.

Craig Foster: You just

feel totally different.

It is just, and you feel sad that,

you know, so many people will

not be able to experience this.

You feel, so obviously we

are very privileged, but

it's, it's just so different.

The whole physicality, the

whole mental space is different.

Utterly is a different person there.

And what it does is it starts

to break down the self and you

start to feel part of everything.

And you don't feel that that, that

that sharp, nasty taste of the ego

in your mouth it, it naturally breaks

that down and softens everything.

And I love the way the, your

neuroscientist friend has, has articulated

that because it's exactly the case.

It, it, it fundamentally changes

one, and it's not surprising.

I mean Sure.

We've had you talk about, you know.

The last 10,000 years of this

sort of much harsher ancestry

post agricultural revolution.

But one doesn't think about the

3 million years of fully wild

living that comes before that.

That's a much deeper memory.

That's a much deeper in our psyche.

That's what we, who we really are.

Forget about this last few

seconds of 10,000 years.

That's really what we are about.

And that's where I think we

desperately need to draw our, our, our

inspiration from as we move forward.

Rupert Isaacson: Conflict resolution

again, because I, I guess if it's, if

it's healing conflicts within oneself,

whether it's the conflict of the self,

that horrible little voice always

telling you your shit, there you go.

Or the exhausted muscles around the

eyes squeezing the eyeballs because

they don't get a chance to relax even in

somebody who's grown up like George has.

You know, because long before George

got to Yellowstone National Park, he was

exploring the forests of New England.

You know, it's, it's not like George

wasn't in natural environments, you

know, and yet even those of us who can

access them we still suffer because so

much of our time is, has to be spent.

Engaging economically.

And isn't it interesting that, as

you say, Craig, the 3 million years,

and of course there are still people

on the planet who are living in that

3 million year old authentic way.

Yeah.

It's easy to forget that, you know,

we'll be often reading books, you

know, our hunter gatherer ancestors.

It's like they're still there.

Craig Foster: Yeah.

We, we un contacted wild people living.

It's, it's incredible.

They're still there.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

It didn't go anywhere.

We just stopped listening.

But the,

if they are conf, if the whole

point of that culture is conflict

resolution, because when you're not top

predator, your only hope is strategy.

Together, together,

together, love communication.

If you fragment, if conflict gets

beyond a certain point, everyone's

gonna get eaten by the ness.

Which is of course what we're

facing on a meta level as a

species now with our conflicts.

And we can all become extinct and

become eaten by the hyena, as you

say, different types of hyena.

So much of it still comes down to, to

this idea of conflict resolution and

what, what you were saying earlier

that love, if we're a species of love,

we talk about we're a storytelling

species, but what is story beloved?

I remember once I was on on Table

Mountain and this is when I was 25 and,

so obviously back in the Plato scene

and I, I came down with a fever and I

went up Tableman with my cousin Simon,

who's actually still a psychiatrist in

Cape Town area and his flatmate Lni,

who's a now psychiatrist in London.

And it was on a few times in my life

I've ever actually become delirious.

And then I was like, shit, how

am I gonna get down, right?

Because, you know, table mountain.

Okay, so I've gotta think now and

I've got to try to be, and I'm in an

altar state of consciousness before

I kind of knew what that word meant.

And as I'm coming down the mountain in

this altar set of consciousness, this

thought comes to me where I remembered

in the chapel at school, there was

this, why did it come into my mind?

Then in the chapel in school,

there was a inscription that one

often sees on the wall of a chapel,

God is love and love is God.

And I remember as a kid

thinking, yeah, that's true.

You know, just in the way

that, yeah, that's true.

That's true.

Dunno why.

I know that's true, but it's true.

This same thought comes to me as

I'm stumbling now down the mountain.

And as you know, that's a very

powerful place, dramatically.

Table mountain, the two tip

of the continent tip of where

humanity becomes two oceans Meat.

Yeah.

Whatever.

And I realize, oh, well if God

is love and love is God, then

everything is God, which means that.

The stones under me.

All matter must be God, which means the

shirt I'm wearing, which is created from

cotton, which is a plan, must be love.

And the paint job on the car down there

that we're struggling towards, which is

coming from chemicals that come from rocks

that are matter created must be love.

And the car door that I'm opening

now with the metal that it's made of

and the fossil fuel that maybe it's

not so good, but nonetheless is,

is is a carbon, is is a fossilized.

Forest is love.

Even the gas power in this car is love.

And I thought, well what

about, what about hate then?

What about torture?

What about atrocity?

What about war?

Where's that as?

And then this thought came, ah,

that's twisted forms of love

removed from the source, expressing

insane pain, but it's still love.

And with that, I passed

out, but I never forgot it.

Did I need to be on a place like Table

Mountain to have that revelation?

Talk to me guys about how you've

come to your view of nature and love.

Have you, are there some moments of

epiphany that stand out for you that way?

Kickoff, whoever can bring one to mind.

Quickest.

George Bumann: I talked last, Craig,

Craig Foster: your,

I was looking at you, George.

We make animal sounds

and then we'll forget.

Oh, that's so cool.

There you go.

George Bumann: You have to embarra.

What's that?

That's an elk.

Is it?

Is red stag?

Yeah.

Relative red stag.

Relative of, is it bugling

Rupert Isaacson: or is

it just No, that's a cow.

That's a female's vocalization.

George Bumann: That's a, yeah.

Calling her calf.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Can you just give us the

bugling of the male quickly?

George Bumann: If my

throat's clear enough,

Rupert Isaacson: I can now

see why they call it bugling.

So I often wondered that because you

know, with Red Deer, which is the European

equivalent, they don't make that sound.

It's more like a Yeah, they bark.

Sort of,

George Bumann: Yeah, they roar.

Yeah.

George Bumann: Very un unmanly sound.

When some people hear it for the first

time, they're like, we're, we're expecting

more Like that ro like the bison.

Do you know?

Like, no, that's, that's our a

Rupert Isaacson: You somehow

feel unmanned personally by that.

That's,

yeah.

Anyway.

Yeah.

I digress.

Okay.

Craig, it's all you.

That's a great digression.

Craig, falling in love

with, love with nature.

How did it happen for you?

Craig Foster: So, I think

you know, the, the, the, the, the natural

thing for me when I was younger was to

try and you, you feel that inside you,

you feel that three millennial ancestral

pull and because of the strange place

you grow up in, you've got absolutely

no idea really of how to find that.

So you go for a cliche, you go for it must

be in the wildest, most dangerous place.

So, you know, I started with big

sharks and then progressed to diving,

you know, in giant crocodile layers

going into the down the tunnels in

the avago to the place where these

massive reptiles drag their prey.

Thinking that that one might be a good

place to find what you're talking about.

But because you can only spend literally

minutes in these places, and we are

very lucky to make it out alive.

It's what, what George is saying, you

get absolutely, really no, you get

this unbelievable adventure and in,

in way too much adrenaline, but you

you don't get any of that incredible

detail that he's talking about.

So it was an amazing adventure.

But ironically, I came back here

to the great African Sea Forest and

started studying an animal that you

would think would be very boring

and wouldn't bring you anywhere.

And that's the humble limpet.

This is an animal that kind of looks

like a rocket, doesn't seem to move much.

Rupert Isaacson: Why?

Why did you choose that animal?

Craig Foster: Because

they're so accessible.

You can go down, I can go down every

single low tide and observe these animals.

It's so, so the world hotspot for

limpets, about 25 species or more

from the massive giant limpet to the,

you know, tiny little Yale limpert.

But I was like just watching these

animals day in, day out, day in

out, and not much was happening.

And then suddenly you get these epiphanies

and they take you into their secret lives.

Deeper and deeper, and you

think, okay, I've looked at

them now every day for a year.

That's it.

And then the next day, oh my

goodness, you knew nothing.

And it takes you deeper and deeper.

And they're fertilizing their

gardens at low tide, you know,

pooping on their own lgal gardens.

They're trimming the gardens

just to the right amount.

They're growing certain alies, they,

you know, tender gardens for years.

I mean, it is, you know, incredible

ways of trying to avoid predation,

extreme predators hunting them.

I mean, it's just, there's absolute,

but what is, what happens at a certain

stage, and this is the critical

thing, you suddenly feel like you are,

your consciousness is starting to blend

a little bit with a lipid consciousness.

As hard as that sounds.

This is a mollusk you know,

that lives in a shell.

It's like a snail an ocean snail

of a sort, highly modified.

And then you go into the, you

know, what's growing on the shell.

You've got these marine lichens boring

into their shells and they're building

them up to survive that each, you can

look at each shell and you can tell.

How that animal has lived

in what environment?

By the shape of the shell, by how it's

being carved by the rocks around it.

And what happens is you start to merge

to some degree with lier consciousness.

So, and the, the, the, the,

you feel like you're part of

that intertidal environment.

Somehow, somehow your mind is,

and you can figure things out.

You can think of what it might be like to

be in a storm as a limpert or what it's

like to feed, or how you're dealing with

the sun and the heat, and where all these

biotic pressures are moving you around.

And suddenly you are, you feel the

beating heart of the intertidal

in your own beating heart.

That's very different to going

into a crocodile there a few times.

You know, you, you actually

feel part of this thing.

And that's the critical thing, is

that the sense of belonging, this

is the most key word, belonging.

So you feel that you

belong on this planet.

You're part of it.

You are wild animal in a sense, living

the strange domesticated existence, but